What is Rhythm in Music: How Beat, Tempo, and Polyrhythms Work's

Today we’re going to talk about rhythm, the groovy glue that brings our music to life. Rhythm is one of the three pillars of music, the other two being melody and harmony. We’ve already discussed the other two, and now we’re going to complete the hat trick.

What is Rhythm in Music?

The coolest thing about rhythm is that it’s present everywhere in music, even within melodies and harmonies. Melody notes and chords have to be arranged in some order, and follow a pattern of timing. So a good understanding of rhythm goes a lot further than simply programming drums or learning to clap on beat.

Rhythm is unique because it’s relative to our human perception of time and space. While melodies and harmonies are formed from frequencies and soundwaves traveling through the air, rhythm is relative to the timing of the other musicians you’re interacting with, or itself, if you’re a solo performer.

Different cultures even have different fundamental understandings of rhythm and how it functions in music. Eastern musicians such as those in India subdivide measures and beats in a totally different way than musicians in the West. Both are correct, for the system they work within. For the purpose of this article, we’re going to dive deep into the Western approach.

Why is Rhythm Important in Music?

Now more than ever, rhythm is central to music making, and music’s evolution. For the past several hundred years harmony has been at the center of musical innovation, whether in the counterpoint and orchestration of classical and romantic period composers like Mozart, Beethoven and Debussy, or in the improvisational developments of African American Classical Music (Jazz) in the 20th century.

However, for the past several decades, many musical innovations have come from rhythm. The rise of world music, sample culture and the hip hop revolution spawned a new era of music making, flush with polyrhythms, new art forms (rap lit. rhythm and poetry)

What often separates a catchy melody from a flop is timing. Often a flurry of notes with a static rhythm would be a bore, but rhythmic variation can bring excitement to an otherwise rudimentary melody or chord progression!

Rhythm is often referred to as the “backbone” of music. Without it, the entire thing would fall apart. The responsibility placed on musicians who keep rhythm is equally high. Oftentimes, a great drummer makes or breaks a band, while a musician that has difficulty keeping a steady tempo sticks out like a sore thumb.

The Basic Elements That Comprise Rhythm in Music

Before we start flipping our beats and grooves upside down, let’s look at some of the basics. Having this fundamental knowledge and vocabulary of rhythm will allow you to incorporate new and exciting rhythms into your music freely, as well as communicate those ideas with other musicians stress-free.

Beat

“Beat” has two definitions in music. First and foremost, we use the word “beat” to describe a musical note that represents a duration of time.

We organize music into “measures” (also called “bars”). Within each measure are “beats” that “subdivide” the time within that measure. By placing notes of different “values” inside the measure, we create a modulating pattern of notes, which form the groove.

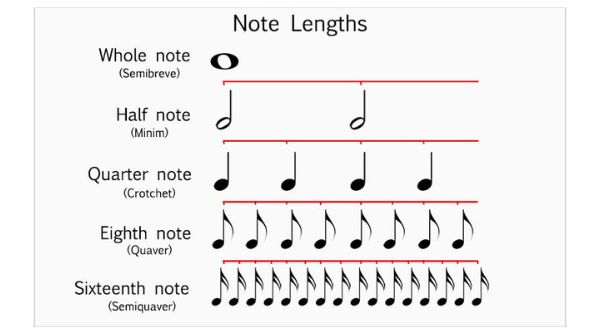

Each beat can be thought of like a pulse, just like the beating of your heart. In a measure of 4/4 time for example, there would be four heartbeats per measure. These are called “quarter notes”. If the heart were to beat twice as fast in the same period of time, we would instead have eight pulses, or “eighth notes”.

If the heart beat twice as slow on the other hand, we’d have two beats, called “half notes”. If there was only one heartbeat or pulse, we have a “whole” note. A whole note takes up the space of an entire measure.

The second definition of beat is a repetitive sequence of notes, normally assigned to some type of percussive instrument.

In Western music, the “beat” as we understand it is normally established by the drums or a drum machine. The other instruments will then play “on the beat” along to the rhythm provided. You’ll often hear musicians say things like, “making a beat”, or “give me a beat”. These phrases refer to a rhythmic groove as a whole, as opposed to the technical term used to describe individual “pulses”.

Time Signature

Whether we are using quarter, eighth, half, or whole notes is relative to the number of pulses contained within the set space of one musical measure. This is established using a time signature. You’ve likely seen time signatures in written music, on table cloths at cafes, or even in video games.

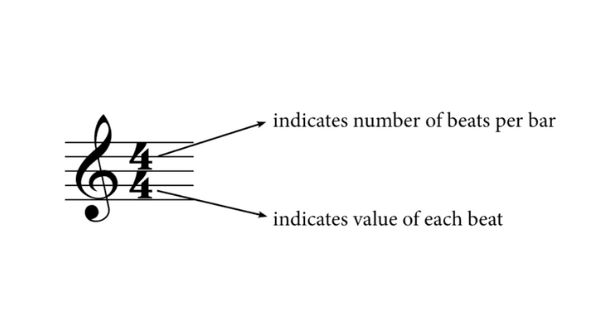

A time signature contains two numbers, one on top and one on bottom. The top number tells us how many pulses or beats are in each measure, while the bottom number tells us which type of note counts as one beat.

For example, in 4/4 time, a quarter note counts as one beat, and there are four quarter notes in each bar.

In 3/4 time, a quarter note counts as one beat, but there are just three notes in each bar.

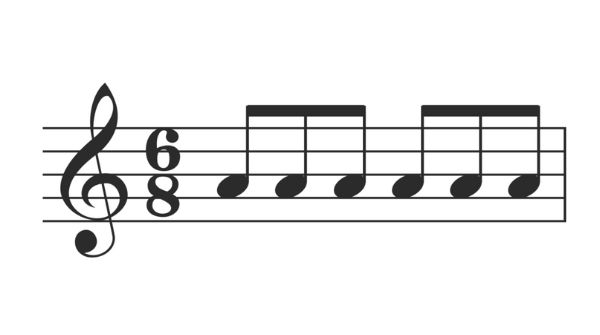

4/4 and 3/4 are called “simple” time signatures. Other, more complex time signatures do exist, called “compound” time signatures. In a time signature like 6/8 for example, there are six notes per bar, except instead of quarter notes, we’re counting in 1/8th notes.

Tempo (BPM)

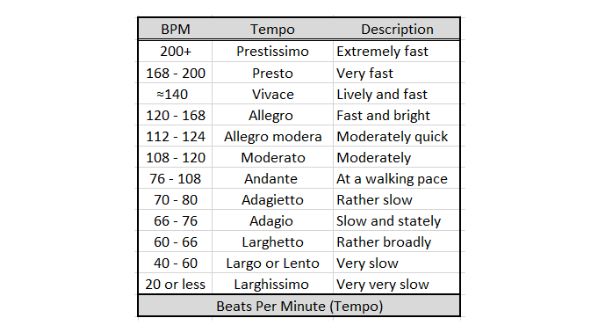

Just as the time signature tells how many pulses are inside of each measure, the tempo or beats per minute (BPM) of a song tells us how quickly the beats are played.

Remember that timing within music is relative. The note value only tells us how much time each note receives relative to the piece’s time signature. Therefore, the same passage could be played faster or slower without a change in the actual written note value.

For example, eighth notes in a measure of 4/4 at 80 BPM would be just as fast as quarter notes in a measure of 4/4 played at twice that speed, 160 BPM.

The notes would still be written relative to the time signature, not the piece’s overall tempo.

Strong and Weak Beats

Now we’re getting into the expressive side of what makes rhythm exciting. Just because there are a set number of beats per measure, doesn’t mean there is only one option when it comes to expressing those beats.

This is where “strong” and “weak” beats come into play. This creates ebb and flow within a measure, so that the groove doesn’t feel like a robot.

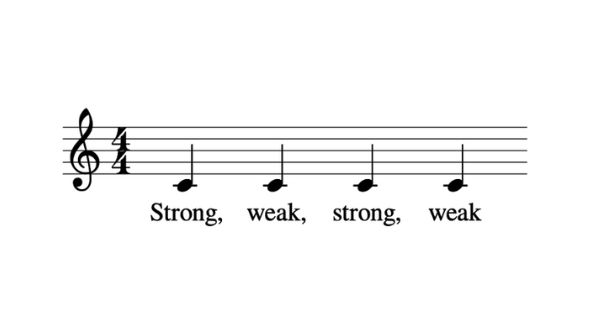

In 4/4 time for example, the first and third beats are normally “strong”, while the second and fourth beats are “weak”.

Listen to one of the most classic 4/4 drum beats to hear this for yourself.

Did you notice how the first and third beats are emphasized by the strong sound of the bass drum coupled with the guitar and bass? And how beats two and four (where you hear the crack of the snare drum) are left empty?

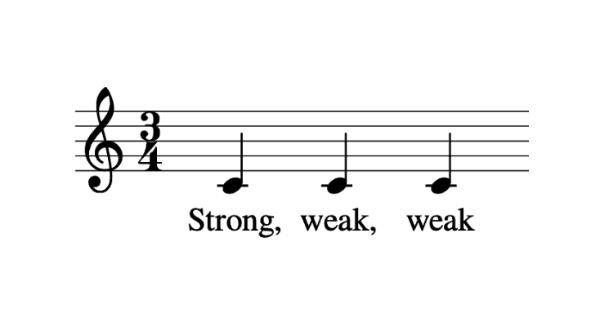

In 3/4 time, beat one is strong, while beats two and three are weak.

Different patterns of strong and weak beats are also used to group music into genres! Rock music for example, was one of the first genres to use a strong-weak strong-weak pattern, while “Waltz” (one of the most popular styles and dances from the 1800s-1900s) exclusively uses a strong-weak-weak pattern.

Meter

Meter is the term we use to discuss how clusters of beats are felt in twos and threes, which make up time signatures.

“Duple meter” is a rhythm with a strong-weak pattern. This pattern can be repeated, but each strong-weak packet is “duple” in nature (a combination of two beats).

“Triple meter” is a rhythm with a strong-weak-weak pattern. This pattern can also be repeated, with each packet being “triple” in nature (a grouping of three notes).

Using meter, we can divide the time within a measure into twos and threes.

For example, one measure of 4/4 time is divided into two “duples”.

On the other hand, one measure of 3/4 time contains one “triple”.

Syncopation

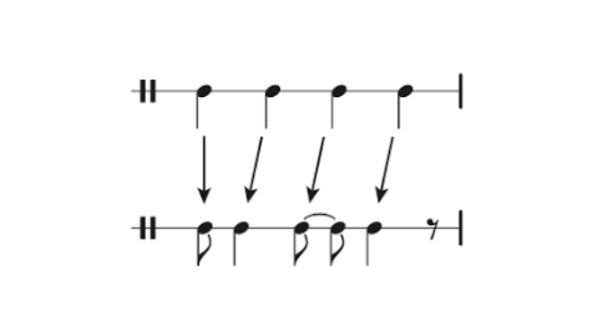

“Syncopation” occurs when we play a separate rhythm that doesn’t align perfectly with the strong and weak beats established by the piece’s time signature and meter.

Music would be boring if the other instruments only followed along to the strong-weak patterns of the drums or percussion, so we use syncopation as a way to add excitement and variation to our music.

You can think of this like a counter-rhythm. In a syncopated rhythm, the syncopated part will play on the weak beats, against the strong-weak pattern in the piece.

Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You” is a great example of syncopation in popular music. Listen to the layers created by the various elements combining into one rhythmic groove.

Accents

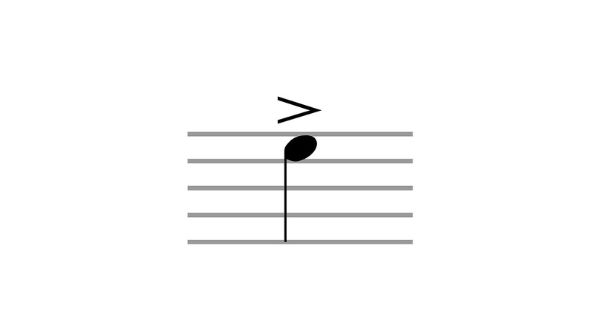

The term “accent” is used to describe which beats in a measure receive emphasis. Accents are another tool used to break up the monotony of gridlocked rhythm.

Normally in a measure of 4/4, the 2 and 4 are accented by the snare drum or other percussion. Where accents are placed in a beat can be indicative of the piece’s genre. For example, in traditional country and western music, the “up” beats are often accented instead of the “down” beats.

Downbeats are those that fall on the quarter note beats in each measure. Upbeats are those in-between, indicated by 1/8th notes.

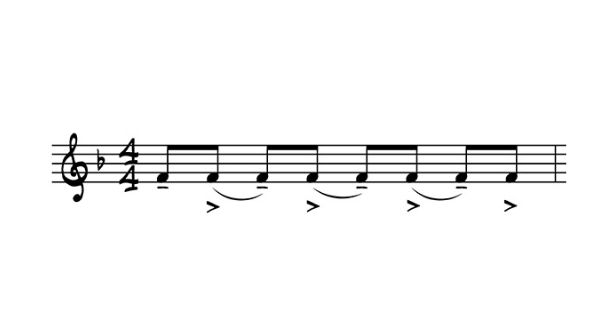

This is a “swing” rhythm, where the accents fall on the 1/8th note “upbeats”, also used in jazz.

Here is an example of an accented “swung” rhythm from the golden era of swing jazz.

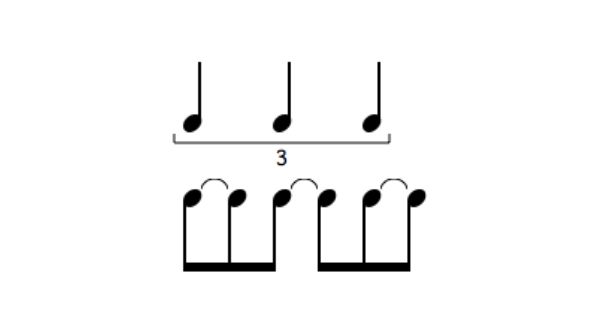

Triplets

In addition to the note values we discussed earlier, “triplets” are a common and important concept used in rhythm. A triplet is when three notes are squeezed into the space normally occupied by just two. The resulting sound is bouncy and useful for creating more enticing rhythmic patterns.

Polyrhythms

Polyrhythms are when two separate rhythms are played simultaneously, creating an interesting and unexpected pattern.

One of the most common polyrhythms is called “3 against 2”. This can also be written as 3:2.

In this polyrhythm, one bar of steady 1/8th notes is played against a bar of 1/8th note “triplets”. As a result, one rhythm will play two notes for every three notes played by the other rhythm, hence the name “3 against 2”.

If you’d like to dive deeper into polyrhythms and how to use them in your music, you can check out our posting on using polyrhythms here.

The Influence of Polyrhythms

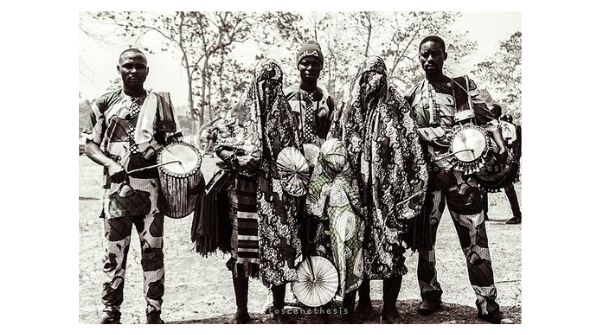

Our modern understanding and use of polyrhythms largely come from sub-Saharan African music brought to the Americas via the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

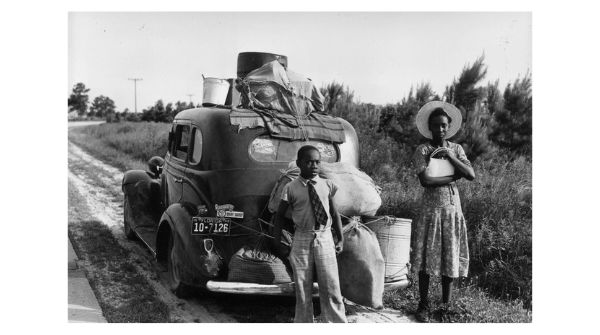

These influences fused with Western (European) harmony and were incorporated into American music in the early 20th century as a result of the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans migrated from the South to larger cities like Chicago, Cleveland, Kansas City, and Los Angeles.

The result was the boom of jazz in the 20s and 30s, electric blues in the 40s, and even Afro-Cuban music (the synthesis of jazz harmony and African rhythms), which skyrocketed to popularity in the 1950s with help from Hollywood, TV, and superstars like Tito Puente, Mario Bauzà, and Dizzy Gillespie.

These cultural shifts opened the door to all modern rhythmic expression, from funk and Rnb, to fusion, rap, hip hop and even progressive metal music!

Appreciating the cultural significance and lineage of these developments is important to not only understand the great artforms that gifted us these concepts and their contribution to art, but also to honor the plight overcome by their progenitors to have these contributions appreciated and recognized.

The Benefits of Rhythm Ear Training

Just like with harmony and melody, ear-training helps us to get better at recognizing, analyzing and communicating when it comes to rhythm.

Many believe that although rhythm and melody/harmony are fused in actual music, they can and should be trained separately. You can think of this like an athlete isolating one particular exercise or training a specific muscle group.

There are two useful types of rhythmic ear-training: dictation and mimicry.

To practice rhythmic recognition, try out our Rhythmania game, where a series of written notes is presented to be played back by sight with the spacebar.

Another type of rhythmic ear-training challenges us to hear a rhythm without notation, and then tap back or reproduce that rhythm in a written form. To practice this skill, give Rhythmic Parrot a shot!

Of course, there are exercises which combine both rhythmic and melodic or harmonic dictation. These should be attempted only after you have strong understanding and recognition of both individually.

The world of rhythm in music is expansive and fascinating, and always offers something new to learn. As musicians in all genres continue to evolve and push the boundaries of space and time, new ideas emerge and blossom. Stay curious, and keep your ears sharp. We can’t wait to hear what you come up with!

Comments:

Aug 19, 2022

Aug 19, 2022

Aug 19, 2022

Login to comment on this post