The Chromatic Scale? Here`s What You Need to Master It

Chances are you’ve stumbled upon the word “chromatic” at some point during your musical adventures. Whether in a YouTube video or from your cool friend who loves talking about jazz music, the concept might have made your head spin.

Fear not. We’re here to explain everything you need to know about the chromatic scale, how to play it, and how you can use it in your creative process right now!

What Is a Scale?

A musical scale is a sequence of pitches according to a scale formula. If the scale goes up in pitch, it’s called “ascending”. If the scale goes down in pitch, it’s called “descending”. The most widely known musical scale is the “major” scale (also called the Ionian mode). If you’ve ever sang “Do Re Mi”, you’re already familiar with the sound of the major scale. To hear it, check out our scale analyzer!

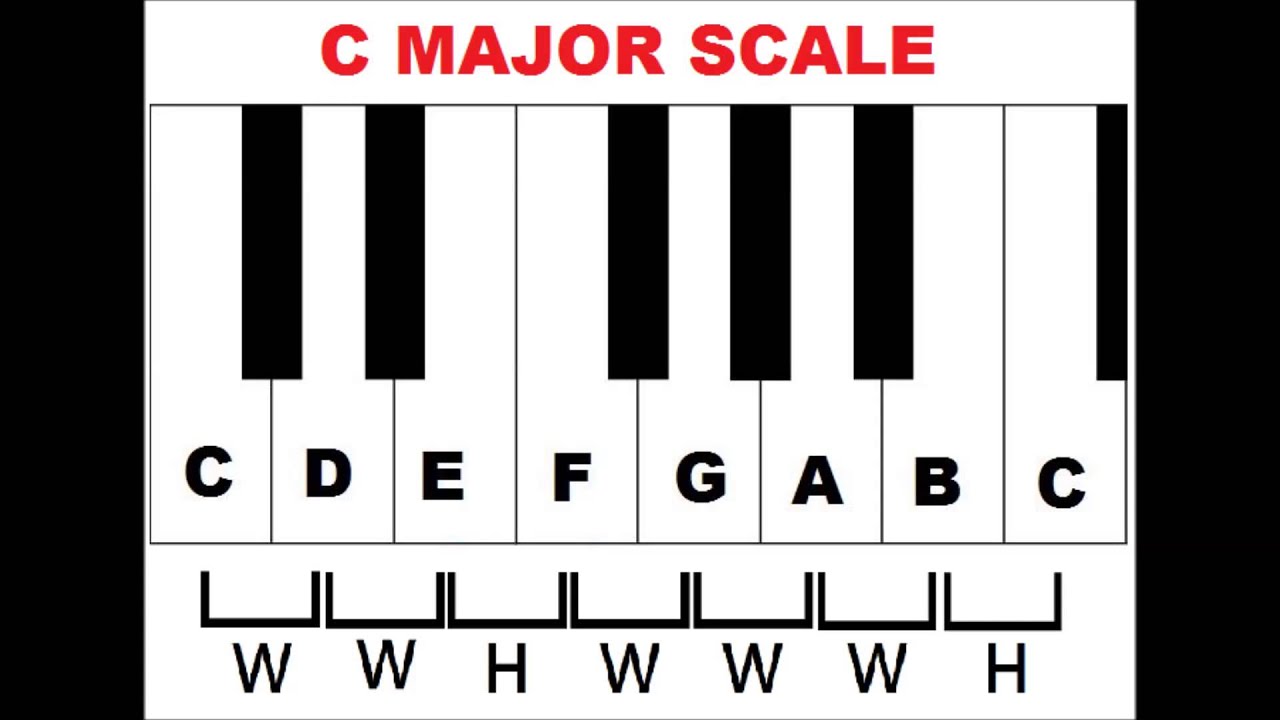

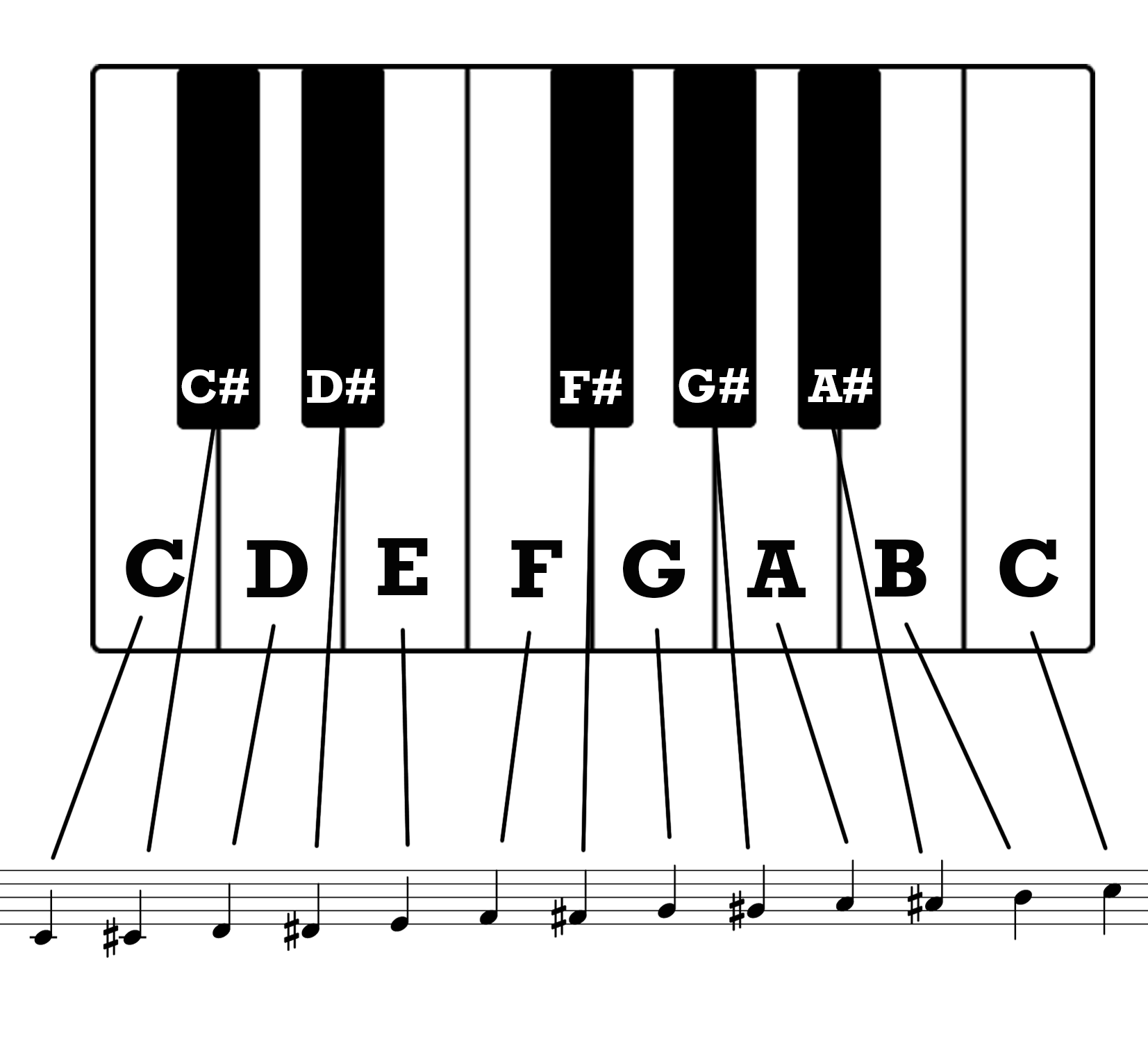

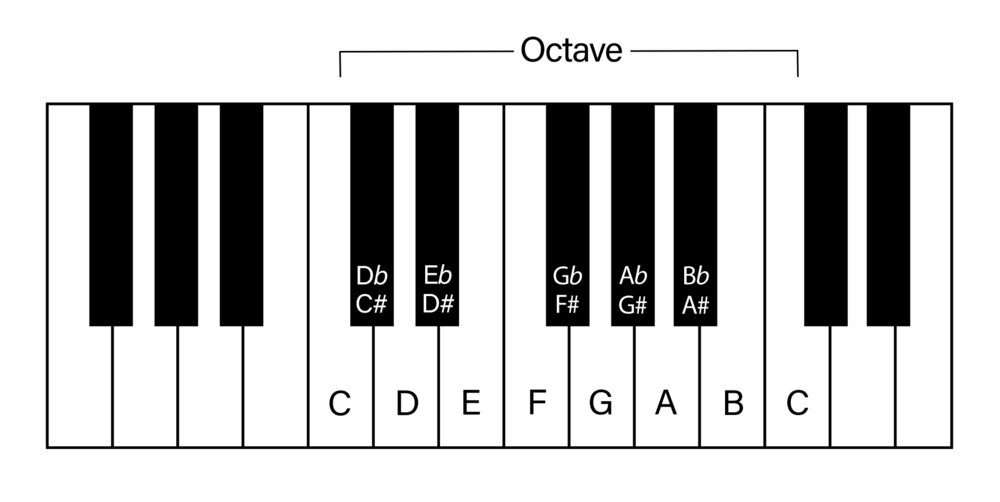

In Western music there are 12 possible notes. The major scale contains seven of those notes. To build the major scale, we begin on any note and apply a formula of half-steps (one piano key or guitar fret) and whole-steps (two piano keys or guitar frets).

The formula for the major scale is Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half or WWHWWWH.

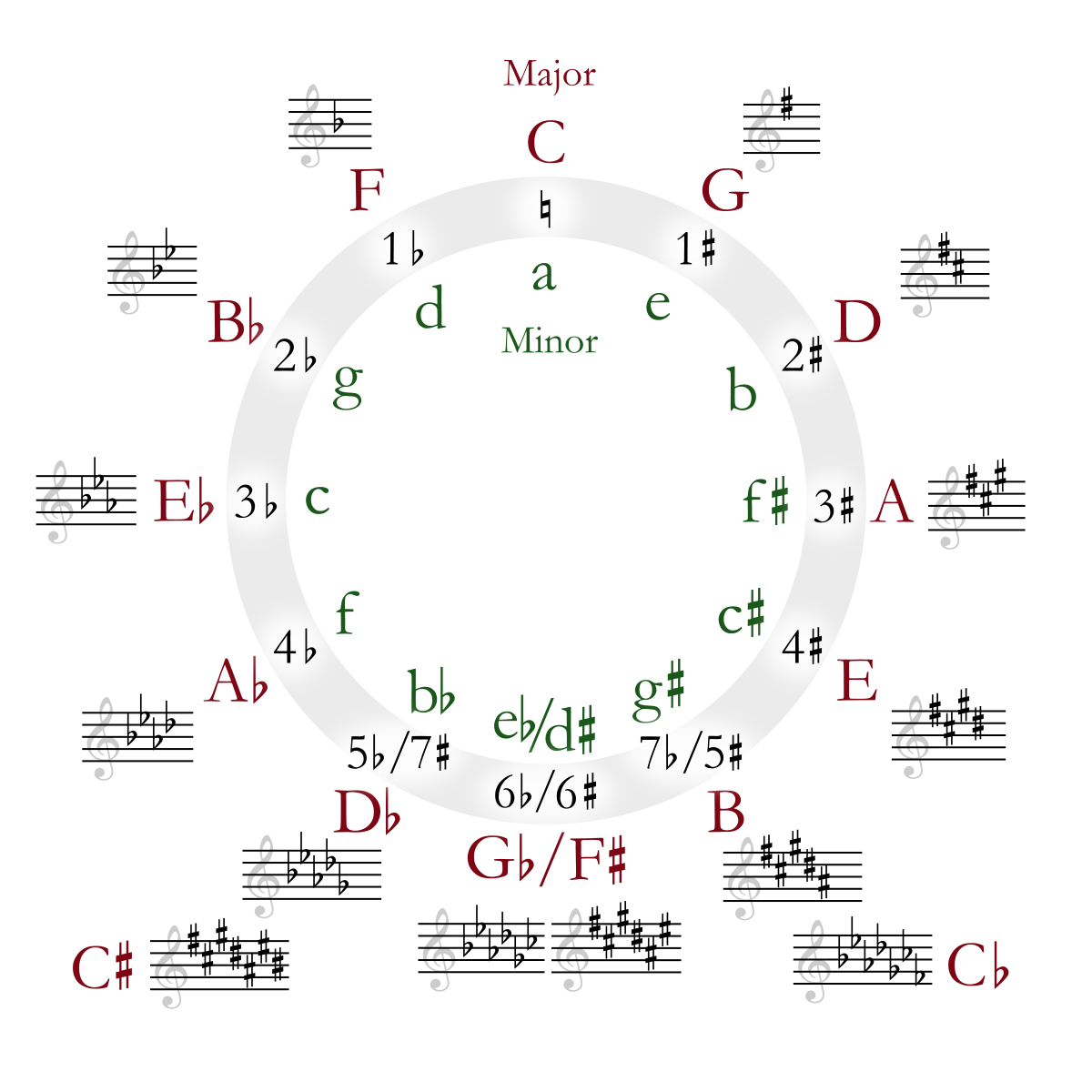

Using this formula, a different major scale can be built on each of the 12 notes, giving us 12 different musical “keys”.

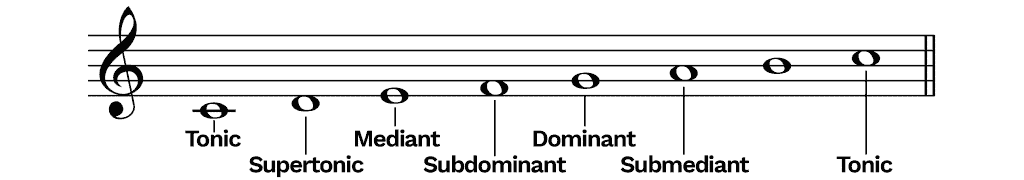

The first note in the scale is called the “tonic”.

If we start and end the scale on a note beside the tonic we create a “mode”. A mode is like an inversion of a scale. Playing the scale this way changes the sequence of half-steps and whole-steps, which makes the mode sounds unique, even though we’re technically playing the same notes.

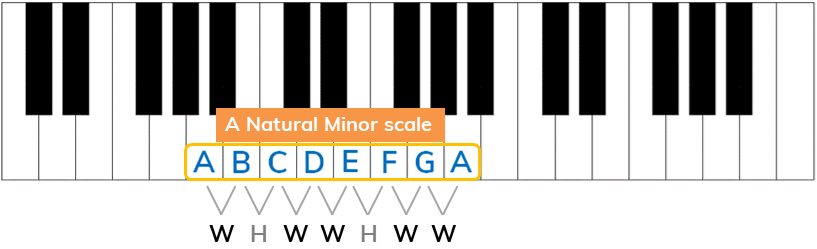

Other scales, like the minor scale (or Aeolian mode) use different formulas of whole and half-steps.

Scales and modes that use this seven-note formula are called “diatonic”. So… what if we built a scale with more than seven notes?

What is a Chromatic Scale?

Unlike the diatonic scales we just discussed, the chromatic scale contains all 12 notes in order.

The Chromatic Scale: A, A#/Bb, B, C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab

Instead of following a pattern of intervals or steps, the chromatic scale simply consists of every available note.

This is all of the white and black keys on the piano. Or every note from the open string to the 12th fret on a guitar.

Because the chromatic scale isn’t built with intervals, it doesn’t gravitate toward any particular tone or cadence. This makes the scale sound unresolved and can add exciting tension to a musical passage or song.

Chromatic Scale Examples

None of this chromatic scale mumbo-jumbo means a thing if we can’t hear it in the context of music we know and love. Before we dive deeper into chromatic scale theory and how to play it.

“Master of Puppets” is having a huge moment right now with the popularity of Stranger Things 4, and it also happens to be a fantastic example of a heavily chromatic guitar riff. If you’ve tried playing it recently, you’re well aware of its unusual fingerings and chord patterns.

“Master of Puppets” is a great example of both the ascending and descending chromatic scale. The opening riff descends, while the second riff that comes in around 0:22 uses an ascending chromatic line.

Zeppelin’s epic 1969 track “Dazed and Confused” is another classic example of a chromatic riff in popular music. It uses two chromatic note “clusters” to emote its signature brooding and foreboding sound. The sound of the descending chromatic scale perfectly outlines the sound and feeling of a relationship falling apart.

Korsakov’s “Flight of the Bumblebee” is probably the most recognizable and classic example of the chromatic scale, while also being one of the most overplayed and hard listen pieces of music in existence.

Many instrumentalists have used this piece as an exercise or to prove their mettle and technique nonetheless.

Chromatic Solfège

Do - Re - Mi - Fa - Sol - La - Ti - Do!

This ^ is solfège.

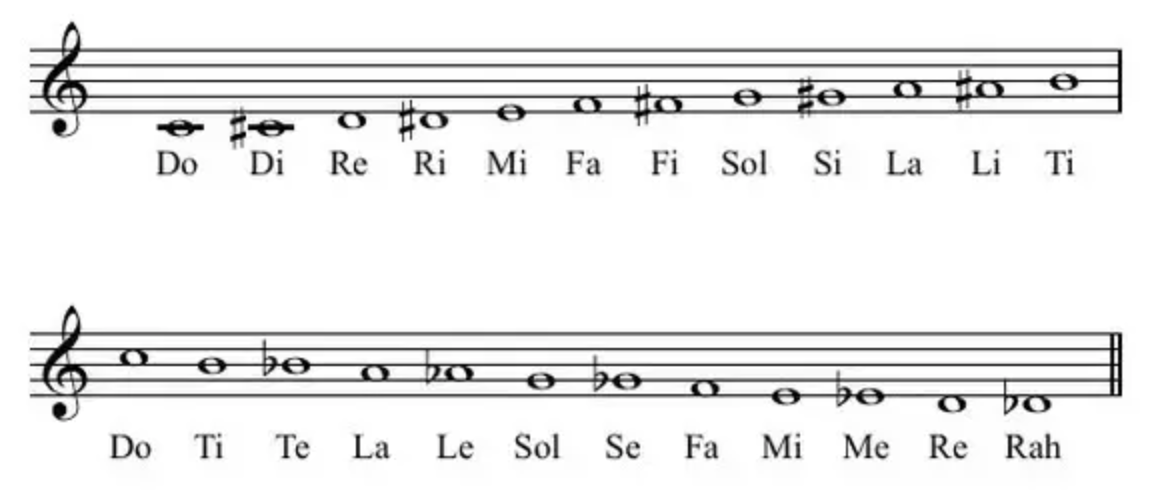

Solfège is a system of sight-singing music. In solfège, we attach a syllable or sound to each pitch in a scale so that we can more easily sight-sing written music aloud.

Just like diatonic scales, the chromatic scale can also be organized this way.

Here is a helpful chart to familiarize yourself with chromatic solfège.

Chromatic solfège follows an easy pattern. For the in-between notes that are sharp (#), we use the same syllable as the previous note with the “i” vowel.

“Do” one ½ step up is “Di”, while “Re” becomes “Ri”.

When we descend and use flats (♭), we use the “e” vowel.

“Ti” one ½ step down becomes “Te” and the note ½ step below “La” becomes “Le”.

The only exception is “Rah”. Because “Re” already uses the “e” vowel, the note one ½ step below “Re” is pronounced “Rah”.

How Many Different Notes are in The Chromatic scale?

Like diatonic scales, the chromatic scale has 12 inversions or modes.

Ironically, if we begin and end the chromatic scale on a note besides the tonic, we’re basically just playing a new chromatic scale beginning on that note. However, it’s still useful to practice these!

How to Play the Chromatic Scale on a Piano

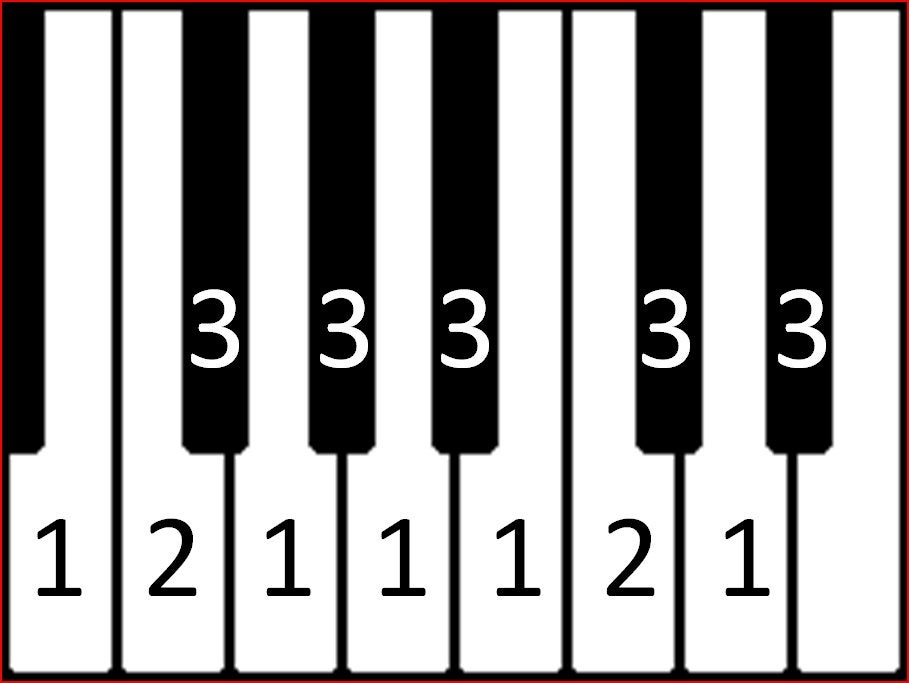

If you’re unfamiliar with the chromatic scale the scale fingering may feel strange at first, but with some slow and deliberate practice you’ll be breezing through them in no time.

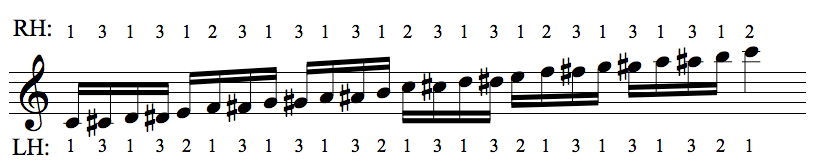

Here is the right hand fingering for the chromatic scale. Do you notice a pattern? Here are a few helpful tips to remember when practicing…

Right Hand Tips:

- If you’re moving from a black key to a white key, use your third finger then your first finger.

- If you’re playing two white keys in a row, use your first finger then your second finger.

The left-hand fingering for the chromatic scale is similar to the right hand with one difference… the consecutive white key fingering if flipped.

Left Hand Tips:

- If you’re playing two white keys in a row, use your second finger then your first finger.

Remember to take your time and practice with a metronome. If you rush and don’t pay attention to the proper fingering, you might cement a bad practice habit that will be twice as hard to break later.

How to Practice the Chromatic Scale on Piano

Here are some helpful patterns you can apply to your exercises when learning and practicing the chromatic scale on piano.

Parallel

To practice the chromatic scale using parallel motion, play the scale while ascending or descending with both hands in unison.

Contrary Motion

To practice a scale using contrary motion, play the scale with both hands in unison, while one hand ascends and the other descends.

For example, the right hand can ascend while the left hand descends. You can flip the hands for extra practice.

Sequencing

To practice practicing in sequence, play three notes of the scale at a time per hand.

Practicing in all 12 keys is always helpful when learning any new scale or exercise. Not only does this help our technique by requiring us to master different fingerings, it’s also a great brain and ear workout for mapping our instrument.

Intervals

Although the chromatic scale isn’t comprised of intervals, you can practice alternating throughout the notes using intervals like thirds, fifths and sixths. Try it out!

Improvising with the Chromatic Scale

Practicing chromatic scales is a great way to elevate your improvisations and jazz lines as you develop a framework for connecting chord and scale tones. Chromaticism is one of the hallmarks of a jazz or “outside” sound, and something you can start incorporating into your playing immediately.

When improvising with the chromatic scale you’ll want to play about three chromatic notes in a row. This works well in genres like blues, funk, RnB, and jazz.

If you play five or more chromatic notes in a row, you’ll be adventuring into some very progressive territory, so make sure that your parts and solos serve the song and style you’re playing!

The Music Scales Tool

Just like intervals, chords, and rhythms, scales can be learned and identified by ear. To practice your scale recognition, test your might with our suite of scale testing games!

Learning more about chromaticism will open up new pathways and musical doors as you progress on your journey as a player, composer, or producer and provide some exciting new possibilities for you to explore.

Stay curious and keep your ears sharp, and we can’t wait to see your progress on the ToneGym leaderboards!

Comments:

Login to comment on this post