What Is an Interval in Music? Exploring the Spaces Between the Notes

As a musician, there's nothing quite like the feeling of hitting the right notes at the right time. But have you ever wondered what makes those notes "right"?

It's all about intervals!

Intervals are the most basic building block of music theory.

In this article, we'll explore the concept of musical intervals, and unlock the science to the magic between the notes.

What is an Interval?

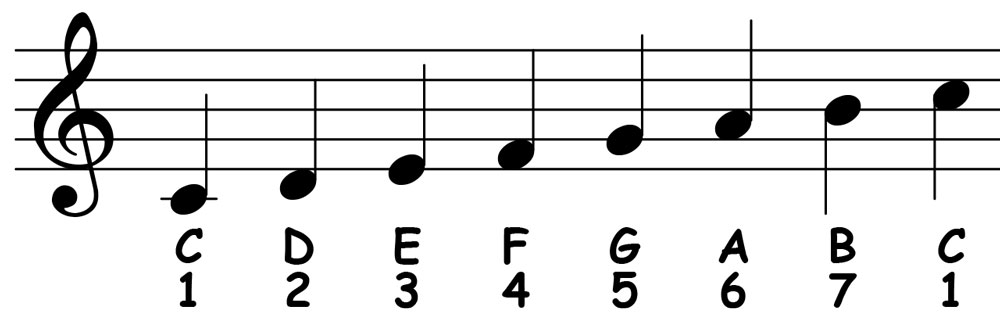

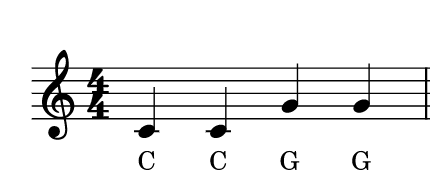

An interval is simply the distance between two notes. This distance is measured in steps, or "half-steps" (also known as "semitones") on the keyboard or fretboard of a guitar. Each step is equivalent to one key or one fret on the instrument. Two semitones equal one whole tone or “whole-step”.

For the sake of convenience, we use the term “whole step” to describe a jump of two piano keys/guitar frets and “semitone” to describe the distance of one key/fret.

Interval Names

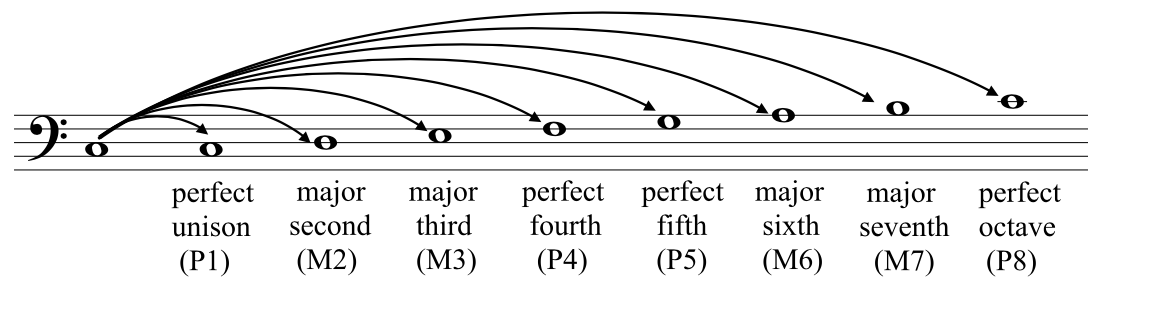

Quality

Degree

PERFECT INTERVALS:

Intervals that can have a major quality are the second, third, sixth, and seventh.

Most notably, the distance between the first two notes in a 3-note major chord are a major 3rd, which gives the chord its name.

Major intervals tend to sound uplifting and optimistic, adding a sense of brightness and energy to the melody or harmony.

The beginning of the song "Happy Birthday" features a major third between the notes C and E.

MINOR INTERVALS:

Any major interval can be lowered (♭) by one semitone to create the equivalent minor interval.

The interval keeps its degree name, but with a minor quality.

For example, the interval of a major third is four semitones (C - E). If we lower the “E” by a semitone to “E♭” we get a minor third.

This applies to the other major/minor intervals as well:

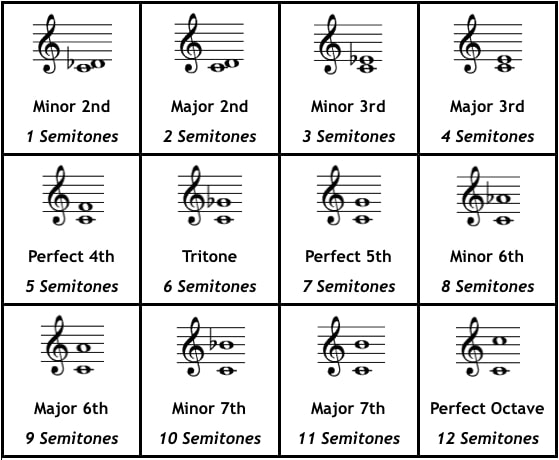

Minor 2nd = 1 semitones

Major 2nd = 2 semitones

Minor 3rd = 3 semitones

Major 3rd = 4 semitones

Minor 6th = 8 semitones

Major 6th = 9 semitones

Minor 7th = 10 semitones

Major 7th = 11 semitones

For a minor interval, the shorter distance between notes creates a darker sound that most people associate with melancholy or introspective sounds. The beginning of the song "Greensleeves" features a minor third between the notes B and D.

AUGMENTED INTERVALS:

Remember those perfect intervals we discussed earlier? What about… imperfect intervals?

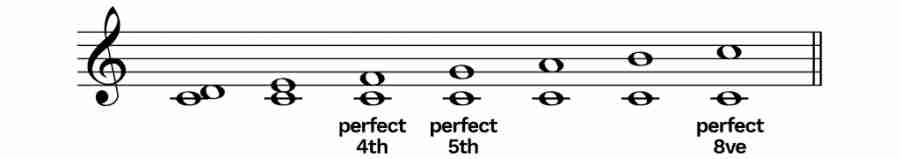

The perfect intervals can also be raised or lowered to have a different quality, while retaining their degree.

These intervals are no longer consonant, they are dissonant, meaning they long to resolve back to another consonant interval in the key. Musicians use these sounds to create tension and release.

Augmented intervals are created by raising (#) a perfect interval by one semitone.

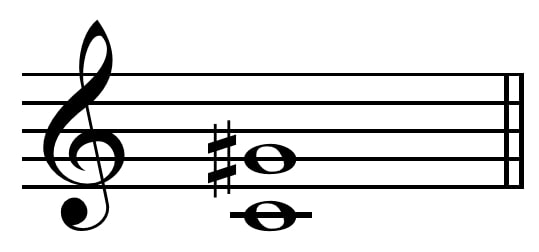

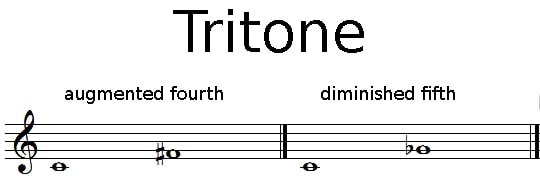

For example, a perfect fourth can be raised by one semitone to create an augmented fourth.

This interval has a very tense and dissonant sound, and it is often used to create tension and suspense in film scores and modern music. The “Simpsons” opening theme uses this interval to create its quirky, off-kilter sound.

The perfect fifth can also be augmented. Paired with a major third, this interval forms an augmented chord.

An augmented chord is spelled like this: 1 - 3 - #5

DIMINISHED INTERVALS:

Diminished intervals have a very tense, unstable sound. They are created by lowering an interval by one semitone, most commonly the perfect fifth.

This interval, the diminished 5th, is called the “tritone”. The tritone is infamous for being especially dark and anxiety-inducing.

The opening notes of Beethoven's famous "Moonlight Sonata" feature a diminished fifth interval, which creates a sense of unease and tension for the listener.

Listen here:

This interval is found in a diminished chord: 1 - ♭3 - ♭5

Nomenclature

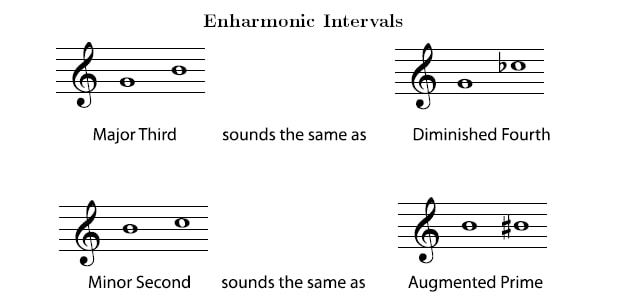

Some intervals are “enharmonic”, meaning they sound the same but can be spelled differently, depending on the context, like the English words “write” and “right” or “aunt” and “ant”.

For example, an augmented 5th could also be called a minor 6th. In the context of the basic minor scale, we use “minor 6th”, because the scale already contains the interval of a perfect 5th.

Similarly, a diminished 4th is just a minor 3rd. Using “minor 3rd” in most contexts is more common.

Typically, a scale or chord can only contain one of each degree.

The “Lydian” mode of the major scale is a great example.

Lydian: 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7

Because the #4 is enharmonically the same as the ♭5 you could spell this scale:

1 - 2 - 3 -♭5 - 5 - 6 - 7

However, for the sake of mathematics; musicians and theoreticians don’t do this! Instead, the framework of the 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 pattern derived from the basic major scale has to be kept in tact.

To facilitate this, the 4th degree is raised (#) while the perfect 5th remains.

Detecting Intervals by Ear

Now that you understand the basics of interval names and qualities, how can you start identifying intervals by ear? The first step is to familiarize yourself with the sound of each interval.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to find musical references that are familiar to your ears, like timeless or TV theme songs.

For example, “Here Comes the Bride” begins with a perfect 4th. If you hear an interval and associate it with the song, you’ll have a point of reference to recognize the sound.

“Somewhere Over The Rainbow” begins on a perfect octave.

You can build this muscle from the ground up on ToneGym with the Departurer game.

With practice, you'll be able to identify intervals in real music and use them to improve your playing and writing.

Here are a few quick tips to help you get started

1. Is the interval consonant or dissonant? Does it sound pleasant or is it harsh?

2. Is it a wide interval or a small interval? If you notice a big distance between the notes, it’s likely a perfect 5th or higher.

Some of the easiest intervals to recognize are the minor 2nd and the tritone. This is because these intervals are especially harsh and can’t help but to stand out.

The minor 2nd is the theme music from the movie Jaws. You can’t miss it!

The tritone is best remembered using the Simpson’s Theme or Maria from West Side Story.

Intervals that are further apart tend to be more difficult for many people to distinguish. The minor/major 6th, minor/major 7th, and octave are murky.

If you’re a half-way decent singer, there’s one trick you can use to suss out these intervals. Sing an octave and let your voice descend downward, landing on the note you’re hearing to match the pitch. Count the number of steps you descended and you’ll have an answer.

For instance, if you sing an octave and descend by one semitone, you’ve found a major 7th. Two semitones would be a minor 7th. Three a major 6th.

Already mastered identifying intervals by ear? For an added challenge, you can also practice identifying chord inversions.

Test your mettle on ToneGym with the Inversionist game.

Intervals are the building blocks of music, and understanding them is essential for any musician.

By recognizing and using intervals in your playing and writing, you can better convey your feelings through music. Not only that, you’ll be more efficient, better connected to your material, and gain skills like sight-singing/reading, transcription, and audiation.

So next time you play or listen to music, pay close attention and see if you begin to hear new things!

Comments:

Oct 22, 2023

Oct 20, 2023

Oct 19, 2023

Login to comment on this post