June 22nd, 2023

What is a Tritone? How to Use Music`s Most Nerve-racking Interval

You’re streaming your favorite show, something shocking happens, and for dramatic effect, you hear the legendary sting, “Dun! Dun! Dun!”.

This cliche is found everywhere in recorded media, from old radio broadcasts to early TV and noughties comedy movies. But why does it grab our attention, without fail, every time?

The answer: it’s a tritone.

The tritone is music’s most nerve-racking interval. It’s dissonant, unresolved, and grating… and when used properly, can lead to a satisfying build up and resolution.

In this post, we’ll explore what the tritone is and how to use it in our music making.

What is an Interval?

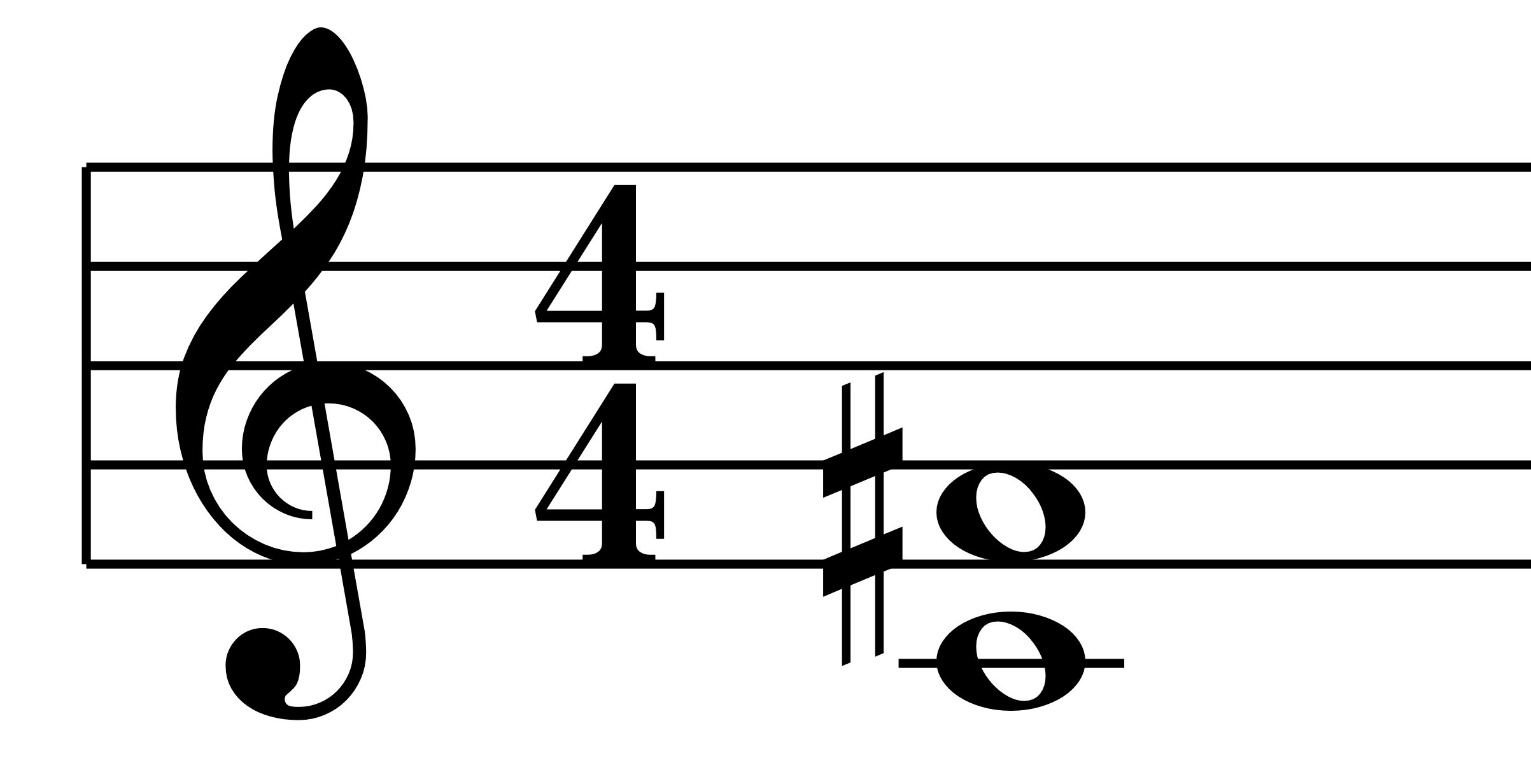

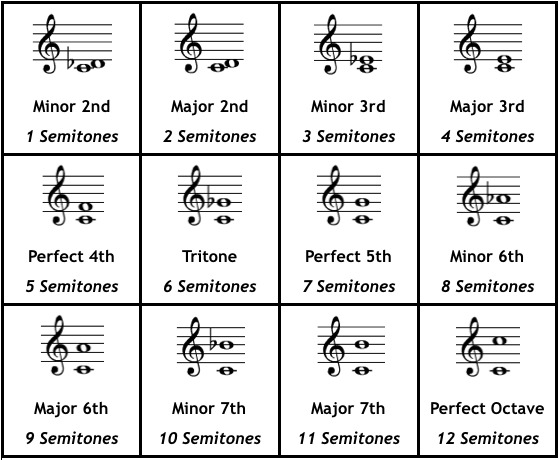

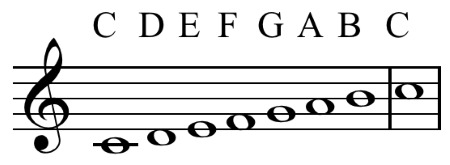

An interval is the distance between two musical notes.

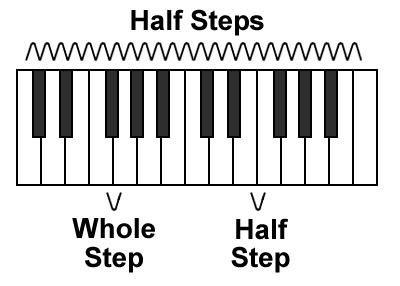

Intervals are built from whole steps (two piano keys or guitar frets) and half steps (one piano key or guitar fret).

A quick note! The term “tone” is used to describe a musical pitch, while the term “note” is actually used to describe the written down version of that sound on a musical score. For the sake of clarity, we’ll simply use the word “note” to describe both.

Different intervals have different sound qualities based on their relationship to one another. Each note produces a different frequency, when those frequencies resonate together, a new “compound” sound is produced.

Intervals fall into two groups: consonant and dissonant.

A consonant interval is a stable, pleasant sounding interval that doesn’t need to move or “resolve” back to another interval, like a “Perfect 5th”, which is seven half steps… “C” to “G”.

A dissonant interval is less stable and discordant, and therefore feels like it wants to resolve back to a “safe” consonant interval. An example of a dissonant interval is the minor 2nd, which is just one half step, as in “C” to “D♭”.

Minor 2nd: Jaws theme!!

Intervals get their names from the musical alphabet:

A - A#/B♭ - B - C - C#/D♭ - D - D#/E♭ - E - F - F#/G♭ - G - G#/A♭

A “Perfect 5th” for example is five letter names away, like “C” to “G”.

The interval of a 2nd would be two letter names away, like “A” to “B”. Whenever there are accidentals like # or ♭, the interval can be divided in two.

“A” to “B” is a “major 2nd”, while “A” to “B♭” is a “minor 2nd”.

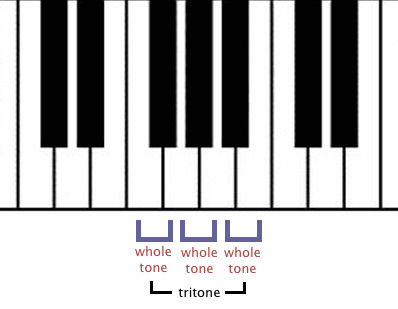

The distance of a tritone is three whole steps or six half steps between two notes.

If you’re into etymology, you’ll already see from where the tritone gets its name!

“Tri” + “tone” = 3 whole tones.

It’s important to pause here and explain the nomenclature (musical vocabulary) that can be used to spell or discuss the tritone. In jazz harmony this interval is often labeled as the♭5 (diminished 5th). Its enharmonic equivalent is 4+ (augmented 4th).

These terms all refer to the same dissonant interval we commonly call the tritone, but are used interchangeably for different musical/theoretical purposes.

Why is Tritone unique?

If we divide an octave equally in half, the midway point is the tritone!

Contrary to what you might think, this absolute division does NOT create a pleasant sound. In fact, it gives us the most dissonant interval in music.

Tritones typically aren’t used by themselves, unless for dramatic effect (like the sting) or to craft an intentionally discordant musical part.

Instead, they serve several musical functions which we’ll take a look at now!

Tritones in Scales

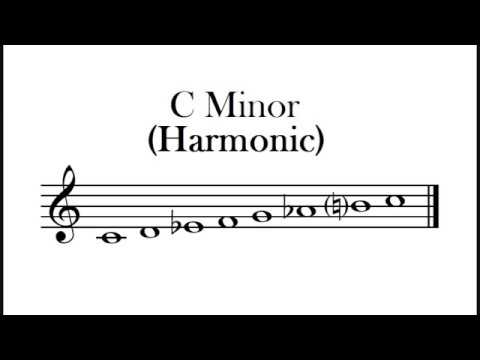

The tritone appears in many scales including the standard major/minor scales and their modes.

Between the 4th and 7th notes in the major scale, and between the 2nd and 6th notes in the minor scale.

When using the harmonic minor scale, an additional tritone appears between the 4th and 7th.

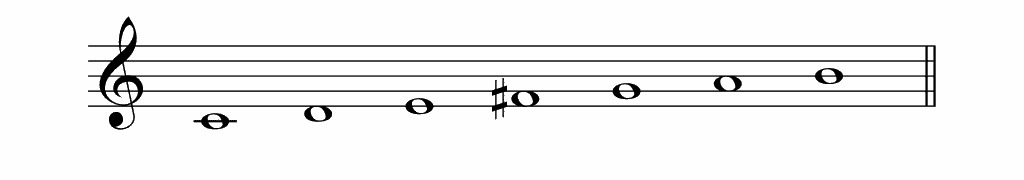

The diatonic “lydian” mode contains a famous tritone within a major scale. The lydian mode is a major scale with a raised 4th scale degree. While this interval would technically be called an “augmented 4th”, it’s enharmonically equivalent to the tritone because it sounds the same (like the words aunt and ant, or which and witch).

Lydian Mode:

In the hexatonic “blues” scale used by blues, rock, and RnB musicians, the tritone can be used in passing during a solo or melody to evoke tension and add depth to a basic pentatonic riff or melody.

You’ll likely recognize this sound from “The Simpsons” theme song: The Simpsons Opening Credits and Theme Song

All that being said, the tritone isn’t typically exaggerated to the point of creating the jarring and recognizable tension we associate it with.

So how do we isolate the special quality of the tritone and use it when creating actual music?

What are Tritones Used For?

1. Tritones create tension and resolution

Much of the satisfaction derived from listening to music comes from a concept called tension and release. Certain “unstable” musical intervals build sonic tension, which is then released on the next chord or series of chords.

This ASMR-worthy payoff is at the crux of how music makes our brains light up.

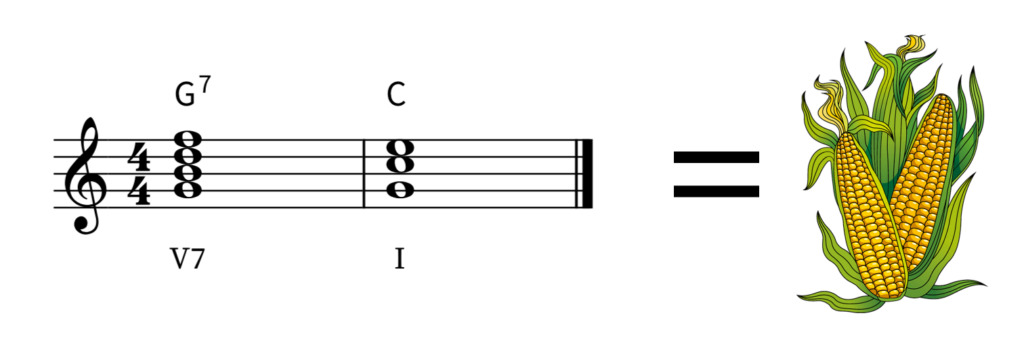

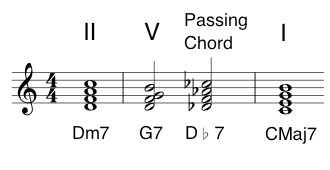

In Western harmony, the most common cadence (chord resolution) is the V7 - I. This is called a perfect cadence.

There is a tritone in the V7 chord!

In the key of “C”, the V7 chord would be “G7”. If we spell out G7, we can see there is a tritone between the 3rd and ♭7th, “B” and “F”.

G7 = G - B - D - F

^tritone^

These notes satisfyingly resolve by half-steps to “C” and “E” when moving to the I chord “C major”.

This V7 concept is also what gives us the groundwork for the famous tritone substitution!

More on that in a few paragraphs…

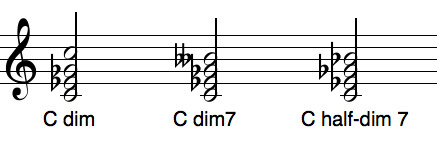

Another example of the tritone creating tension and release is the oft-used “diminished” family of chords (diminished, half-diminished, diminished 7th, half-diminished 7th). These chords all contain a tritone interval between the root and the♭5. The presence of the tritone gives this chord group their signature harsh quality.

These chords can be used as “passing chords” to resolve to another consonant (major/minor) chord one half-step above or below.

This releases the dissonant tension created by the tritone found in the diminished chord.

2. Chord substitution

Tritones can also be used to substitute chords in a chord progression.

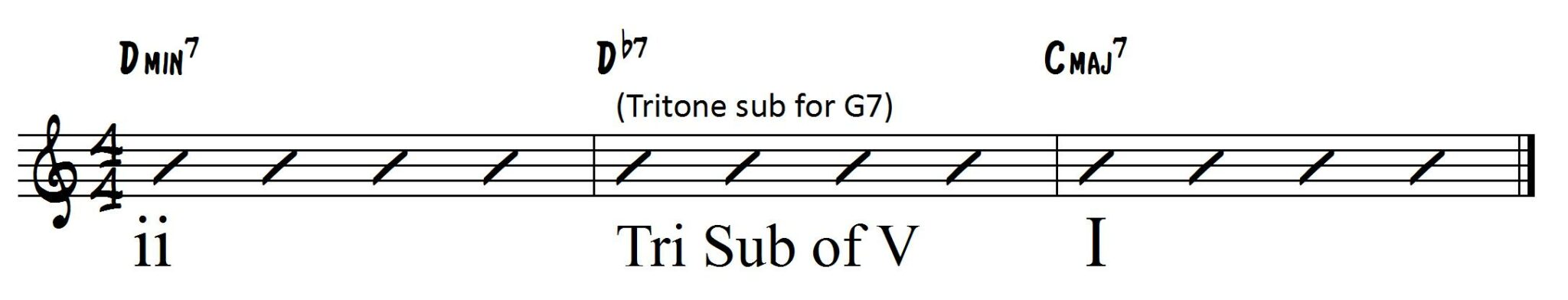

The most common chord substitution used in jazz harmony is the “tritone substitution” or “tritone sub” for short.

This concept is actually very simple! Whenever we see a dominant 7th chord (like G7) in a piece of music, we can swap in another dominant 7th chord starting with the root note one tritone away.

In this case, the tritone substitution for G7 would be D♭7. Resolving to a “C” major chord, this chord substitution adds extra tension and release, not typically found in the diatonic 7th chord.

The reason this works is that both chords share the same tritone interval!

G7 = G - B - D - F

D♭7 = D♭- F - A♭- C♭

The tritone in the G7 chord is found between “B” and “F”. In the D♭7 chord, the same tritone occurs between “F” and “C♭”.

“C♭” is just the note “B”, with a different name for the sake of continuity when spelling out the chord.

This phenomena makes the tritone substitution possible. The chords have enough in common to “function” the same way, while having enough difference to add additional depth and tension to the sound.

Devil's tritone

Somewhere throughout history the tritone became connotatively known as the Devil’s Interval”. An urban legend grew around the Catholic church pursuing an all out ban on its use. Due to its dark and foreboding quality, people tended to associate the tritone with darkness and evil.

While this myth is (unfortunately) untrue, there were rules in the governing musical lexicon of the time that created specific guidelines for the use of the tritone in counterpoint to maintain smooth and proper voice leading.

As music evolved, the use of the tritone did with it. By the early 20th century, African American blues music used this interval to create tension, which as it evolved into African American classical music (jazz) became ubiquitous with the genre and its harmonic structure.

Rock and metal musicians continued to explore the possibilities of using the tritone outside the confines of conventional orchestration, building entire riffs or songs around it, pushing the boundaries of what was sonically palatable for a mass audience, and inventing numerous sub-genres.

By leaning into this sound rather than using it as a passing tool to create consonant resolution, these musicians gave new meaning to the phrase “Diabolus in musica” (Devil in music).

In Hindustani and Carnatic music the tritone is present in many scales as well, sometimes with a fluid quality that changes whether the musician is ascending or descending through the scale.

It’s also found in Japanese pentatonic scales and their modes.

Famous example of the tritone in action:

“Purple Haze” by Jimi Hendrix opens with a powerful dissonant tritone riff:

Black Sabbath eponymous debut track and album is built around a famous tritone funeral dirge:

“Maria” from West Side Story is another example of the tritone used in a melody although the one does resolve one half step above to the perfect 5th:

We’ve only scratched the surface of the tritone and its many fascinating applications in harmony… keep exploring this powerful musical tool and honing your ears on ToneGym!

Comments:

Jul 18, 2023

Jun 30, 2023

Jun 27, 2023

Login to comment on this post