How to Read Key Signatures: The Secret to Understanding How the Music Should Be Performed.

You may have taken a music theory class in high school or college, and probably have mixed emotions about “key signatures” and the “Circle of Fifths”.

These two musical constructs tend to confound new students and for whatever reason, serve as a constant source of frustration and confusion. Fear not, key signatures and the Circle of Fifths that organizes them aren’t as scary as you think, and will actually serve to open your musical mind with a bit of understanding.

Here is a complete guide to key signatures in music.

What are Key Signatures in music?

Key signatures in music are a group of either sharp (raised) or flat (lowered) notes that can be found between the clef and time signature on a piece of written music. Key signatures are a symbol dictating which musical key the piece or musical passage is played in.

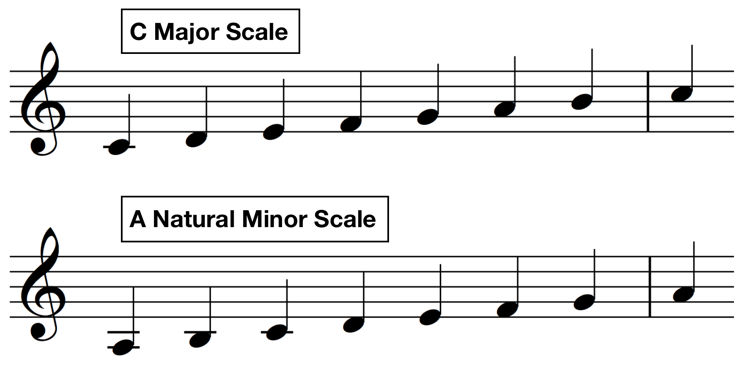

In the Western musical system (as opposed to Panasian and Carnatic/Hindustani systems), scales typically contain seven notes, formed from the 12 available notes. This is called a seven-note “diatonic” scale, taken from the 12-note “chromatic” scale, or musical alphabet.

Different scale formulas (major, minor, dorian etc.) can be applied to any of the 12 notes, creating a varying sequence of notes that are either natural ♮ (G), sharp (G#) and/or flat (Gb).

A musical piece is typically performed using the notes contained within one major musical key, with the respective natural, sharp or flat notes being represented by the key signature itself.

There are 15 key signatures in total, each representing a major musical key. Each major key also has a relative minor key, which contains the same accidentals, just beginning on the tonic of said minor key.

For example, “A” minor contains the notes A B C D E F G, while “C” major contains those same exact notes, simply beginning on the tonic “C” = C D E F G A B. Therefore, these keys are “relative” to one another, and both use the “C” major key signature.

So how do we tell the difference between the two? When reading music, you can typically sus out which tonality the piece is using from observing the first couple of bars. Pay attention to which chords are being played, if the song starts on A minor, or the first few bars contain an “A” minor arpeggio as part of a melody, chances are the piece is based in the relative minor key.

The Difference Between Key Signatures and Keys?

All keys have a corresponding key signature, but key signatures are just written symbols representing the collection of pitches or notes that make up a musical key. Therefore, the terms “key” and “key signature” aren’t used interchangeably.

When musicians discuss music verbally, they typically use terminology like, “the chorus is in F”, meaning the chorus is in the musical key of ‘F’ major. Rarely if ever will you hear a musician say instead, “the chorus is in the key signature of ‘F’ major”.

Why Are Key Signatures Useful?

Key signatures serve several important functions in music. First and foremost, they create a uniform system for organizing musical keys in a way that feels intuitive, with each consecutive key signature gaining or losing sharp and flat notes, or accidentals, as they progress according to the Circle of Fifths.

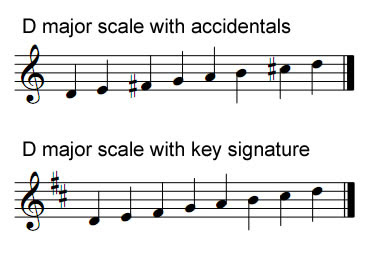

Practically, key signatures alleviate the need to write-in every single accidental, or sharp and flat note in a given piece of music. Without key signatures, written music would be more complex and dense, and much more difficult to read, especially by sight.

Above, you’ll see the “D” major scale written both with accidentals, and inside of the “D” major key signature. “D” major contains two sharp notes, “F#” and “C#”. When written using accidentals, we must add the # sign before the respective spaces for “F” and “C” on the staff.

If the key signature itself contains certain sharp or flat notes, it indicates that the particular note will always be played raised or lowered throughout the entire piece, unless otherwise indicated.

In addition to forming a roadmap of musical keys, these key signatures give us an at a glance tooltip to quickly gathering pertinent information about a specific piece or song, when reading written music notation. With a bit of absorption and memorization, we can learn to glance at a music staff and immediately identify which musical key we will be performing in.

Key signatures also help us to understand scale and chord theory. Each musical key contains seven notes, upon which a chord can be built. The seven chords formed by this system give us the chords we need to form chord progressions, and understand harmony. Each degree of the scale has a numbered name, and a latin name such as Dominant, Mediant and Tonic. If you need a refresher on scale theory or any musical terminology, check out our music theory basics here!

How to Read Key Signatures in Music

Reading key signatures requires a bit of practice, but will intuitively marry with your general musical studies. Over time, you will perform enough music in various musical keys that it will become subconscious.

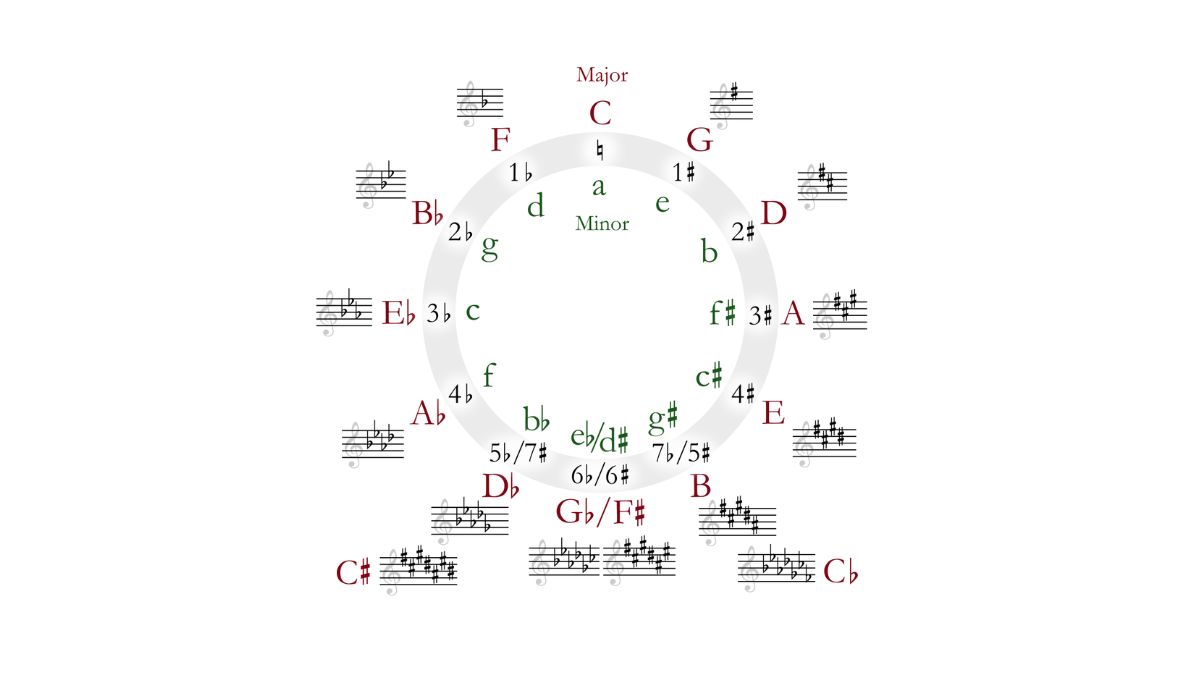

For practical purposes, key signatures are organized in Perfect Fifths, according to the Circle of Fifths. When arranged in this way, each consecutive key signature gains one sharp or flat accidental at a time, making it more intuitive and easier to memorize.

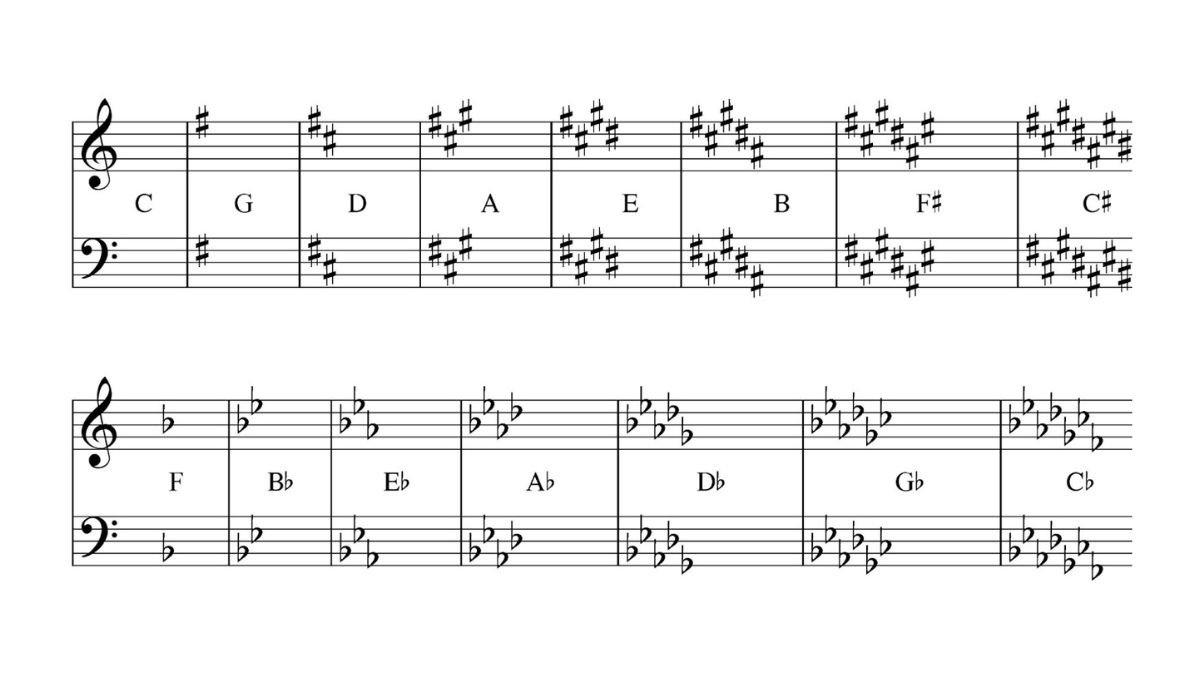

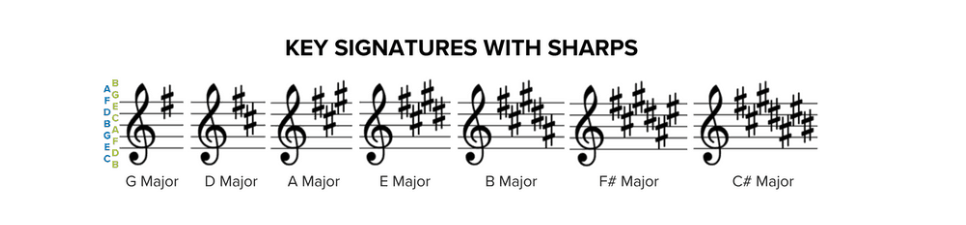

Sharp # Key Signatures

If we move clockwise around the Circle of Fifths, we will find the sharp key signatures.

The key of “C” major is considered homebase when discussing music theory and musical keys. This is because “C” doesn’t contain any accidentals. Therefore, the key signature for “C” major is barren and placed at the top of the circle.

From here we proceed to “G” major, which contains one sharp note, “F#”. This note is taken from two spaces back on the circle.

We continue this pattern for each consecutive sharp key, borrowing an additional sharp note from two spaces behind on the circle.

The sharp note is placed on the line or space of the staff which is raised in the given key. This acts as an indicator that we will always be raising that particular note throughout the piece, thus eliminating the need for writing these notes in my hand every time they occur.

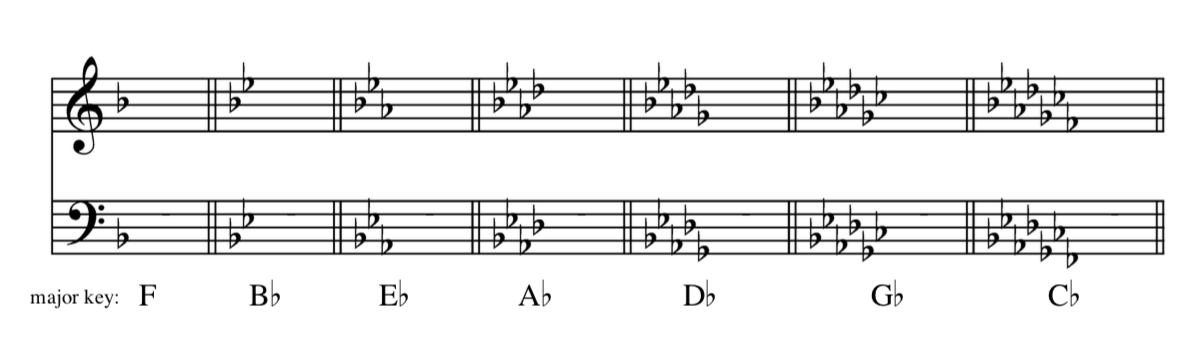

Flat ♭ Key Signatures

If we move backward or counterclockwise around the Circle of Fifths, we have the flat keys. This is sometimes called the “Cycle of Fourths”. A fourth is the inverse of a fifth, so when moving left instead of right, the distance between key signatures in a Perfect Fourth, instead of a Perfect Fifth.

The first flat key is “F”, which contains one flat note. The flat keys follow a slightly different pattern around the Circle of Fifths, borrowing notes in reverse order moving left.

Again, the flat notes indicated in the key signature will be played as accidentals throughout the entire piece unless otherwise indicated.

Functional Practice

At first, reading in key with few sharps and flats will be easiest. “C” major (no accidentals), “G” major (one accidental) and “F” major (one accidental) are some of the easiest keys to read in. You won’t need to do much mental gymnastics when it comes to remembering which notes are raised or lowered in these keys. Once you feel comfortable reading and analyzing music in the above keys, you can try branching out into others with more accidentals.

Some upfront, rote practice will help to solidify the mind/body connection and muscle memory needed to continue reading more complex key signatures quickly. Don’t be afraid to “walk” through a piece, taking note of which lines and spaces receive accidentals, and how that would be played on your instrument. From here, you can branch out into sight-reading and more!

Enharmonic Keys

Some key signatures are functionally the same but can be written in two ways. For example, “Db'' major contains the same notes as “C#” major, just written differently. These are called “enharmonic” key signatures. Think of them like homonyms in grammar… words that sound the same but are spelled differently. Aunt and ant, through and threw, right and write.

When using enharmonic key signatures, it is typical to choose the path of least resistance, meaning the version of the key signature which contains lesser accidentals. “Db” is preferred over “C#” because the former contains five accidentals (D♭, E♭, G♭, A♭, B♭), while the same exact sounding key, written as “C#” contains seven sharps: C#, D#, E#, F#, G#, A#, B# (literally every note).

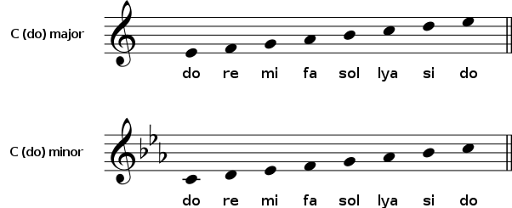

Parallel Keys

Musical keys that share the same tonic but different tonality, such as major/minor are called parallel keys. These key signatures will look drastically different. “C” minor is the relative minor of “Eb” major, so it uses the “Eb” major key signature. This is obviously going to be very distant from the “C” major key signature.

How To Identify Key Signatures

Using ToneGym’s Interactive Circle of Fifths tool, you can explore key signatures in a whole new way.

Recognizing musical key signatures will eventually become an “at a glance” proposition, with the image of each key signature conjuring the knowledge and memory of the respective musical key. The best way to practice is to work on filling in the blanks, taking consistent note of the accidentals in each key when learning a new piece, song, or musical passage. And to actively use resources like ToneGym to improve your overall musical knowledge and theoretical expertise!

Chromatic Notes and Accidentals

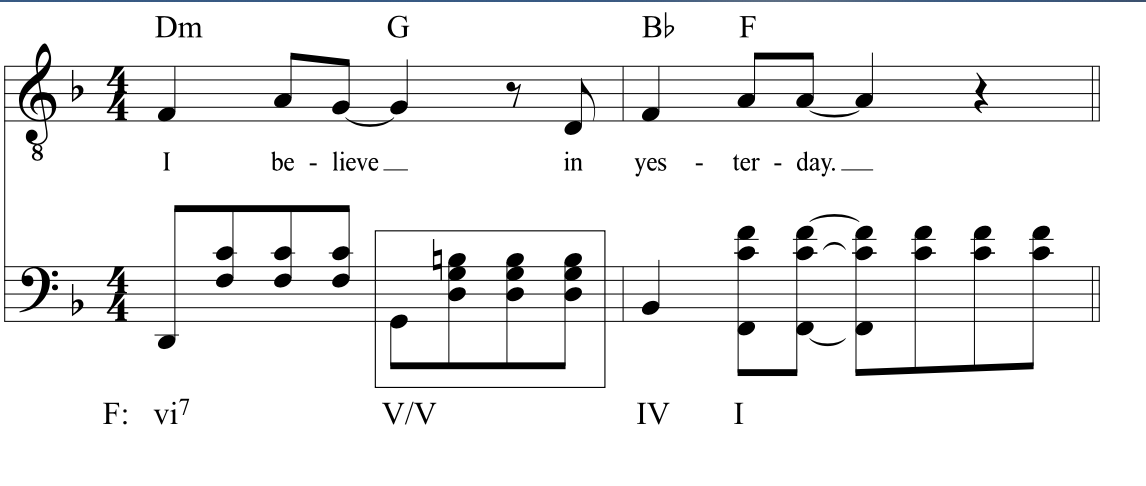

Once a key signature is established, there is no further need to notate any accidentals within the piece. However, if you do see an accidental, it means that this note is “chromatic” or borrowed from outside of the song’s key.

When an accidental occurs, it acts as a modifier to the original key signature, indicating that said note will now be played according to the accidental going forward.

The note will not revert to its original pitch until the original accidental is re-introduced.

As you can see in the above example from the Beatles’ “Yesterday”, the key signature is “F”. The key of “F” major contains one flat note, “B♭”. In the first bar, there is a B natural ( B♮) played by the bass. This is indicated using an accidental. Until we see another “B” note with the ♭ sign placed before it, we would continue to play each “B” note as B♮.

The Stringed Instrument Conundrum

For pianists, horn and reed players, understanding key signatures goes part and parcel with learning to play your instrument. These instruments are not geometrical, or conducive to repetitive “patterns”. The scale that forms each key will have a different fingering or series of pressing down valves and covering holes. Therefore, a fundamental understanding of which notes are sharp or flat in each key is a must. During practice for these musicians, one will often begin to associate each pitch being played with the key signature written on the page.

For guitarists and stringed instrument players however, instruments are geometric, with overlapping scale patterns occurring frequently. Because these instruments are arranged with differently pitched strings horizontally, scales and passages can be easily moved or transposed by just shifting and repeating the same “shape” up and down the instrument's neck. Since the same shape can be played beginning on a different note, stringed players tend not to actively “think” about which notes are altered in a given key. Essentially, one can turn on autopilot and play through scales in every key, without ever stopping to process which accidentals are being used.

While this may sound like a gift, it actually tends to hamper the theoretical development of stringed instrument players.

So, if you play guitar, violin et al., we suggest some active “processing” of the accidental notes inside each musical key when practicing. Just make a mental note of which key you’re playing in and which notes belong to that key, it’ll go a long way to enriching your musical IQ and fretboard/fingerboard knowledge.

We hope you learned a lot from this guide to musical key signatures, and can’t wait to see how you continue to progress with ToneGym!

Comments:

Jan 16

Login to comment on this post