September 5th, 2024

What is a Major Scale? Exploring the Most Powerful Scale in Western Harmony

The major scale. The most powerful tool building block in all of music! Learning about scales is important because different scales evoke different emotions when listening to or composing music.

Quick recap if you’re new… Scales are a sequence of musical notes that go up or down. We build them using specific formulas that date back hundreds of years.

What is a Major Scale?

The major scale is the first scale most people learn when they start playing music. It’s easy to remember and even makes some very big appearances in TV and film.

In Western music there are 12 notes. Scales that are built from seven of the 12 notes are called “diatonic”. The major scale is the most widely known and used diatonic scale. You can even learn to identify the sound of the major scale by ear!

Why is The Major Scale Important?

The major scale is the starting point for learning literally ANYTHING else about how music works. It’s like the ABCs of music theory.

Other important musical elements like chords, melodies, and harmonies all come from scales. So, whether you’re an instrumentalist, songwriter, or producer, the major scale is need-to-know if you want to enhance your musical knowledge and grow your abilities!

How to Build Major Scales?

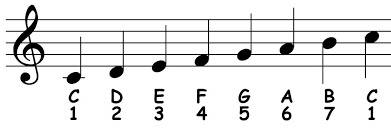

To build a major scale, we choose a starting note. This note is called the “tonic”. To keep things simple we’ll start with the note “C” as the tonic. C major contains no sharp or flat notes (accidentals).

The notes in “C” major are C D E F G A B.

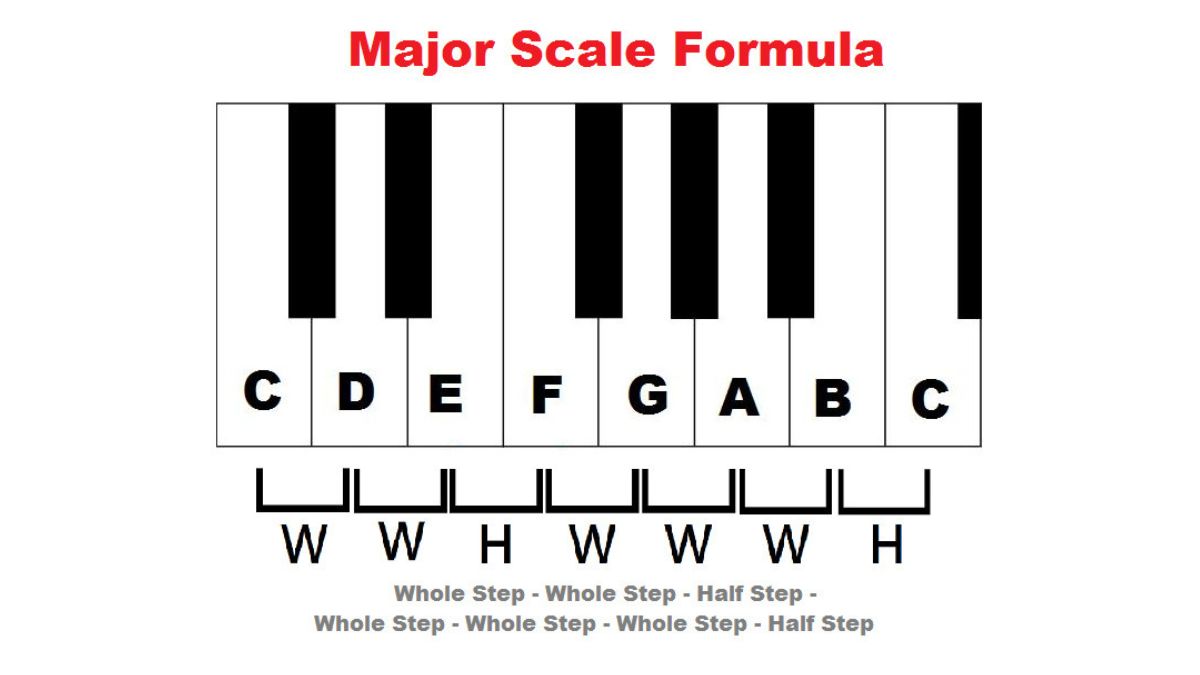

To get these notes we apply a set formula of musical intervals to build the scale from the starting note. These intervals are whole tones and semitones, also called whole steps and half steps.

A whole step is the distance between two keys on the piano or two frets on a guitar, while a half step covers just one key on the piano or one fret on the guitar.

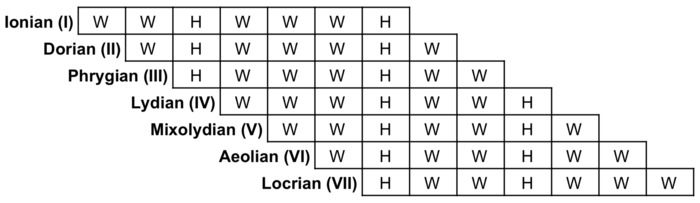

The formula for the major scale is:

Whole - Whole - Half - Whole - Whole - Whole - Half

Oftentimes, this is abbreviated as W - W - H - W - W - W - H.

Another common way of understanding this formula is to give each scale degree a number, 1-7.

This way the major scale is just: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7.

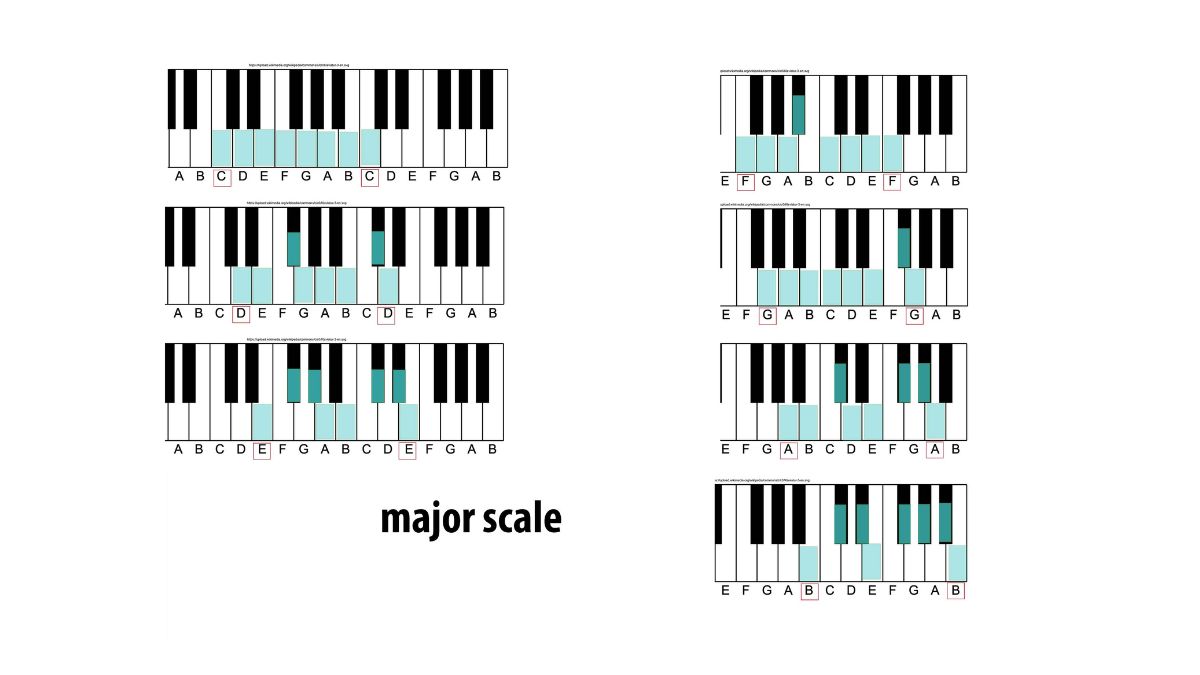

Building Major Scales in Other Keys

Using the same formula of whole steps and half steps we just learned, we can build major scales starting on other notes. For example, if we start on the note “G” and apply the same formula, the result is the “G” major scale.

G - A - B - C - D - E - F# - G

W W H W W W H

To keep the step formula consistent we begin seeing sharp (#) and flat (b) notes appear. These accidentals are easily remembered as the black keys on the piano keyboard. If we start on the note “D” and apply the WWHWWWH formula, we’d produce the “D” major scale.

D - E - F# - G - A - B - C# - D

W W H W W W H

Again, more sharp and/or flat notes appear. This pattern continues as we move away from the key of “C”. It can be difficult as a beginner to do this work in our heads, so feel free to use an online keyboard or MIDI controller to see this in action.

As an exercise, let’s build the major scale starting on “F”, together! Starting on “F” we go up by one whole step (two keys).

F -> G.

Perfect, now we ascend by one more whole step to “A”. Here is the test! The next interval in the formula is a half step (one piano key). Which note is that?

Correct! “Bb”.

Now we have F - G - A - Bb. Next are three consecutive whole steps… C, D, and E. The final half step in the formula brings us all the way home to “F”.

It’s important to practice building major scales like this as an exercise, but you won’t need to do this work manually forever. Musicians learn these scales and commit them to memory.

Eventually, you’ll know which sharps and flats belong to which scale off the top of your head.

In the meantime, one easy way to keep track of different major scales or keys is to use the circle of fifths, which orders the keys by how closely related they are.

Each time we move to the left or right, the ensuing musical key gains one sharp (when moving clockwise) or flat note (when moving counter-clockwise).

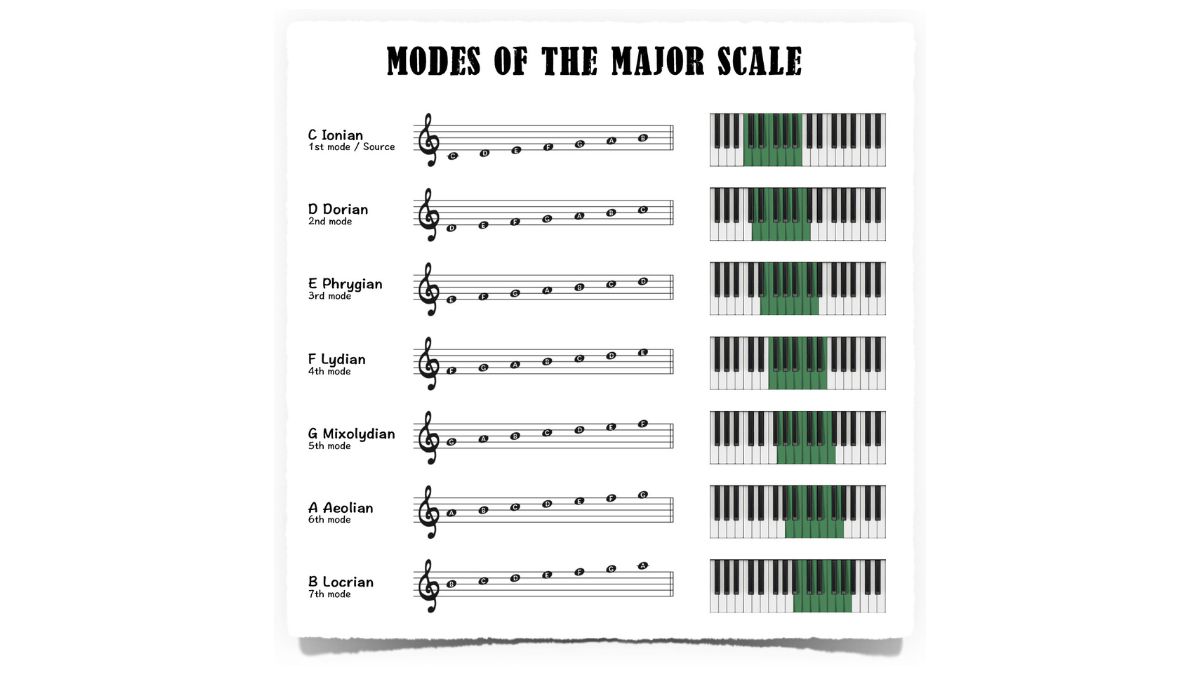

Modes of the Major Scale

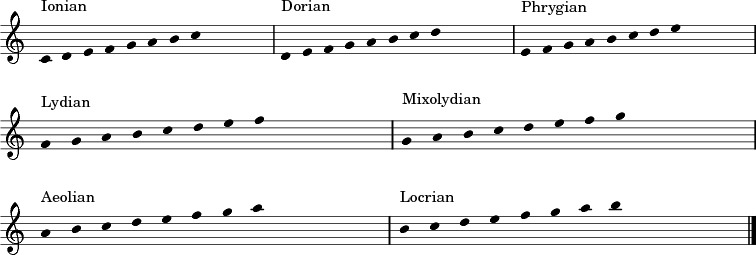

Modes are variations of a scale that produce different qualities or sounds.

If we begin and end the major scale on a note besides the tonic, we get a mode! For example, in “C” major we can start and end with the second note “D” instead.

“D” Dorian Mode: D E F G A B C

When we do this, the order of whole steps and half steps is shuffled around, creating a distinct tonal color. This “mode” of the “C” major scale is called “dorian”. This concept can be applied to any major scale beginning on any note.

If we start on the third note, “E”, the order of whole steps and half steps shuffles around again. Now we have a much darker sounding mode called “phrygian”.

The fourth scale degree “F”, gives us the mystical “lydian” mode. Lydian is actually just like a major scale except the 4th note is raised by a semitone… this combination of a major 3rd with a tritone interval is just magical.

The fifth scale degree “G” is known as the “dominant”. The dominant is the 2nd strongest chord in a musical key and has a unique quality of a b7.

Again, the mode built from this scale degree is nearly identical to the major scale, except the last scale degree, the 7th, is lowered.

Now, we get a beautiful dominant 7th sound.

The next mode, built from the 6th scale degree “A”, is called “aeolian”. You may also know it as the “minor” scale.

Finally we have “locrian”, built from the final scale degree, called the “leading tone”. This mode is not usually used to compose or as a standalone device in improvisation and exists more so as a concept. This mode coincides with the key’s “diminished” chord, but contains two minor 3rds.

The major scale can also be called the “ionian” mode, while the minor scale is also known as the “aeolian” mode.

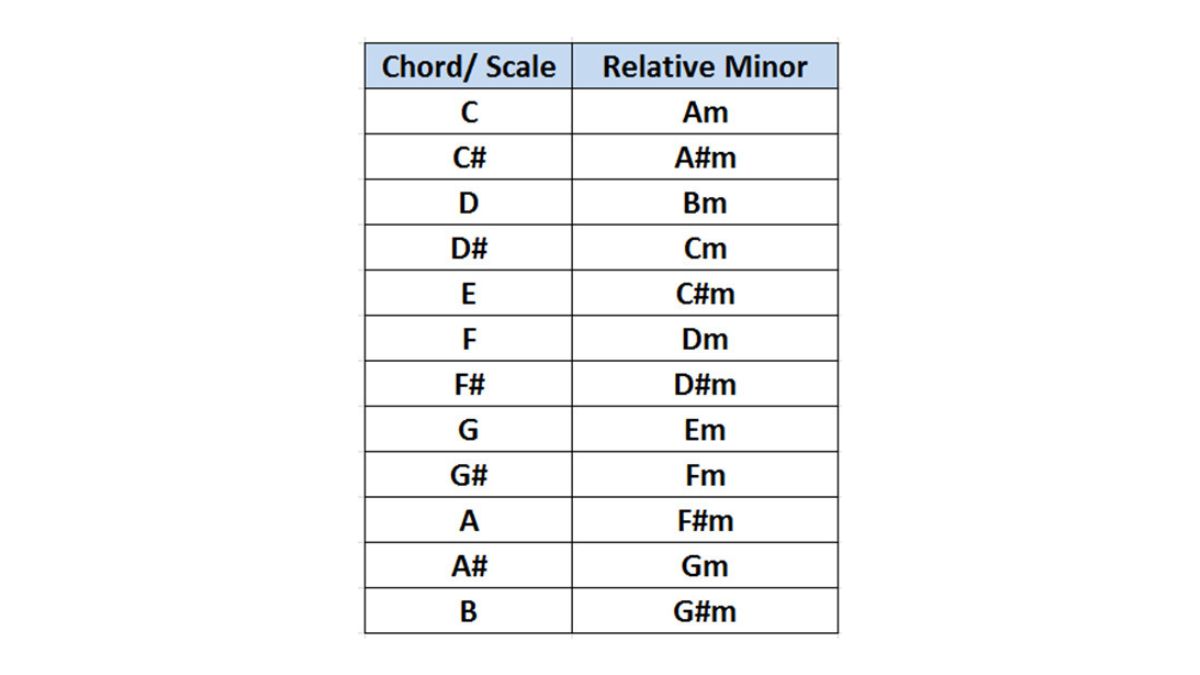

Every major scale has a “relative” minor scale that contains the same notes played in a different order.

In the case of “C”, the relative minor is “A”. To find the relative minor in any key, find the 6th note in the major scale. The mode built beginning on that note is the relative minor.

It’s worth noting that two of the above modes also have a major quality: lydian and mixolydian.

These scales share a major 3rd (four semitones) interval which gives them a definitive major sound. The differences are that lydian has a #4 interval and mixolydian has a b7 (which makes it fit perfectly over a dominant 7th chord or “7” chord).

Modal concepts are a bit more advanced, but worth getting on your radar! Sometimes the major scale itself isn’t the best major mode to play over a major chord. Say THAT five times fast.

These major modes even appear in pop music and TV/film. Just listen to the theme music for the Simpsons to hear the lydian mode in full action:

Congratulations on taking your first step into the larger world of functional harmony! This is just the beginning of an exciting journey to learn and master scale theory. Keep your ears sharp and your mind curious. We’ll see you soon!

Comments:

Login to comment on this post