How to Read Sheet Music: A Beginner's Guide to Musical Notation

Reading sheet music is on its way to becoming an overlooked skill in the modern musician’s toolkit. With so much technology available to compute, compose, and reproduce music digitally, reading is written off by most as unnecessary and archaic. This could not be further from the truth.

Reading music is a widely applicable skill that not only improves your cognition, musicianship, and knowledge of theory, but also boosts your employability and toolkit to make it as a professional working musician.

Whether you’ve been playing by ear, using TAB for years, or are just starting out mixing and producing inside of a DAW, this guide will show you everything you need to know to get started reading notation and sheet music.

What is musical notation?

If we understand music as a language, musical notation is the reading and writing side, while playing and listening to music is the speaking and comprehension side.

Notation is standardized, which allows musicians from all over the world to communicate with one another, regardless of tongue, race, religion, and creed.

Why Learn to Read Sheet Music?

If you’re unsure if learning to read sheet music is worth the effort, here are a few benefits that might help you to commit!

- Makes you a better overall musician.

- It helps you to express yourself more freely and learn new music.

- Improves communication with other musicians.

- It gives you the ability to comprehend music written for other instruments.

- It’s fun!

The Basic Symbols of Musical Notation

Musical notation uses symbols to represent things like pitch, time, and expression.

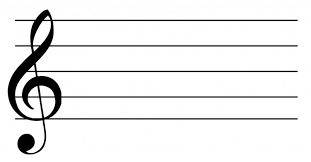

Staff

The staff is the canvas upon which all else is painted. Less poetically, the staff is a series of five lines and four spaces on a sheet of paper.

This type of paper is called “manuscript paper”, and serves as a blank slate for writing musical notation.

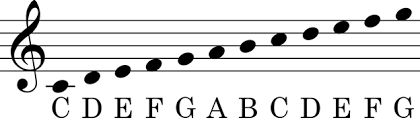

Each line and space on the staff represents a note in the musical alphabet from “A” to “G”.

A circle, called a “note head”, on or in-between the lines tells us which notes are being played, and in which order (moving left to right).

These lines and spaces are enough for all of the white keys on the piano keyboard, but what about the black keys?

Black keys are for notes that are sharp (#) and flat (b). These notes are “in-between” the notes. To represent these on the staff, we simply add the correct accidental before the dot.

Now, how do we know how high or low pitched the written notes should sound? The piano keyboard has 88 keys, and there are only 12 notes, which means the notes repeat seven times. Each time the notes repeat at a higher frequency is called an octave.

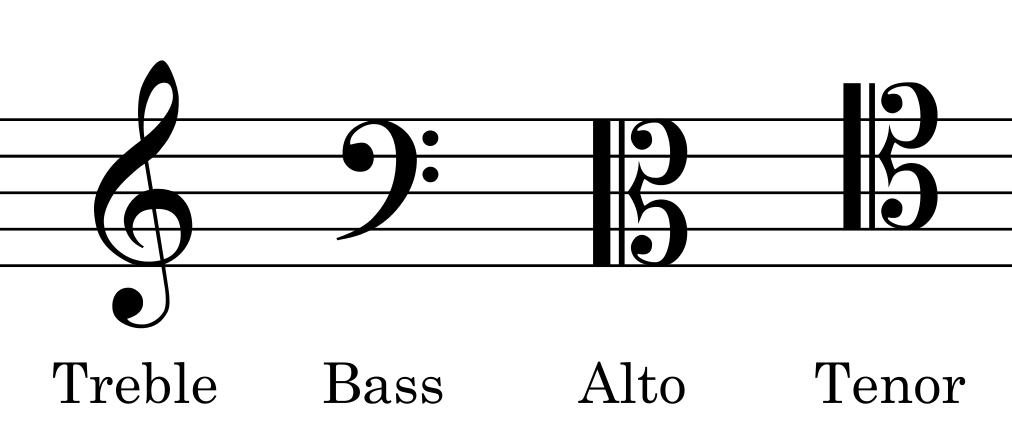

To tell us which octaves the notes are written in, we use clefs. Clefs are symbols written onto the staff that show us the range of the staff, from bass to treble.

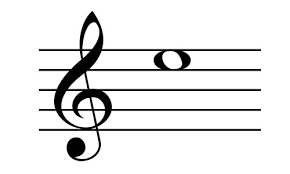

Treble Clef

The treble clef is actually a fancy looking letter “G”, so designed because it wraps around the line for the note “G” on the staff.

Treble clef is used for high-register instruments like flute, violin, and trumpet. Instruments with wide ranges like guitar and piano also use the treble clef.

When reading the treble clef, the notes on the lines are EGBDF, while the notes in the spaces are FACE.

There are plenty of fun expressions to help remember these, like Every Good Boy Does Fine. The spaces are easy enough to remember as the word “face”.

Bass Clef

The bass clef is for low-register instruments like tuba, cello, and electric bass. The piano and guitar also have notes written on the bass clef. The bass clef is a fancy letter “F”, so designed because it encircles the line for the note “F” on the staff.

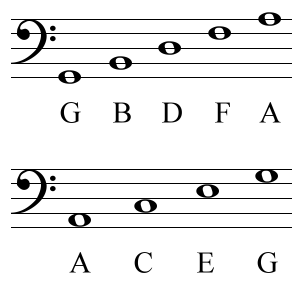

In bass clef, the notes on the lines are GBDFA, while the notes in the space are ACEG.

Good Boys Do Fine Always is a helpful phrase to remember the lines. While All Cows Eat Grass helps us to remember the spaces.

In addition to bass and treble clefs, there are also alto and tenor clefs.

These are “in-between” clefs used by specific instruments like viola and oboe. If you don’t play one of these instruments and are not writing for these types of instruments, you can get started with just bass and treble.

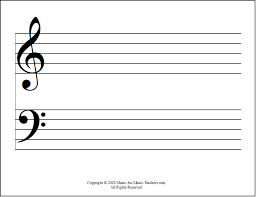

For instruments like guitar and piano, which contain notes in many octaves, a “grand staff” can be used to write music in a wide range.

When reading piano music on a grand staff, the left band normally plays the bass clef part, while the right-hand plays the treble clef part.

Notes and Rest on the Staff

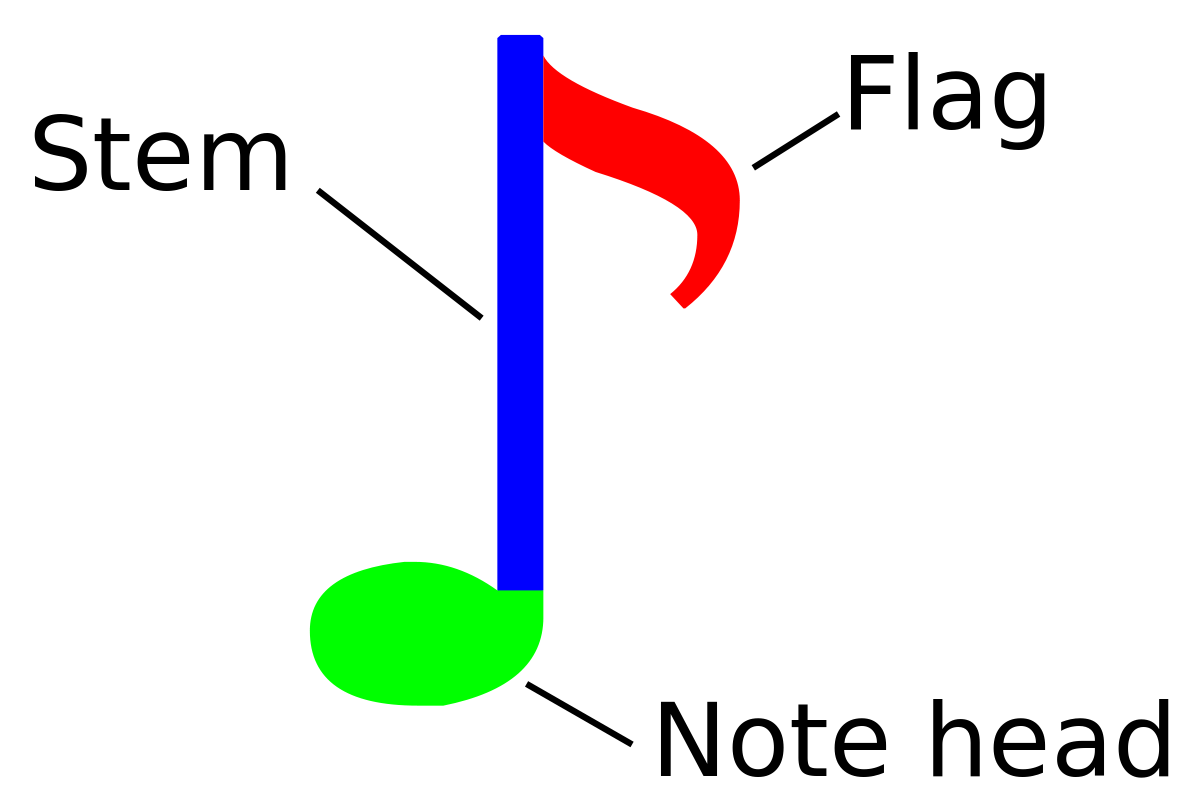

Like we discussed earlier, a circle on a line or in a space tells us which note to play. Sometimes these circles have a line (called a “stem”) attached on the left or right side. These make the notes easier to read.

If a “flag” is attached, it also helps us to read rhythm, which we’ll talk about next.

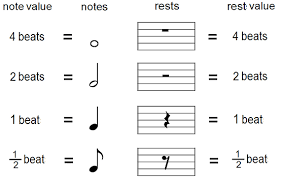

If we aren’t supposed to play for a certain beat or measure, we can notate that with a “rest”. A rest is a symbol that tells us to be quiet.

Rhythm Notation

Now that we understand how to read pitch, we’ll need to learn how to read time. Rhythmic notation tells us how long to sustain each note before moving onto the next one.

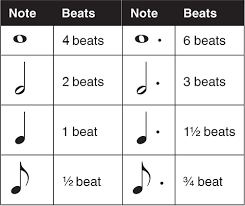

Notes and rests can last for different periods of time or “duration”. To notate time we use things like heads, stems, flags, dots, and ties.

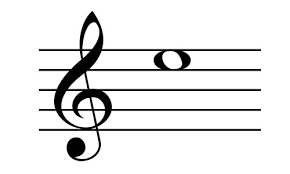

A “whole” note is an empty circle without a stem or a flag. This note lasts for the entire measure.

If we add a stem to the whole note it becomes a “half” note. This note is worth two beats (half the measure in 4/4 time).

If we fill the note in, we have a quarter note. Quarter notes are worth one beat in 4/4 time.

If we add a curvy flag to the stem of the quarter note it becomes an eighth note. These are half as short as quarter notes.

These are all you need to know for basics, although even shorter note durations exist, like 16th and 32nd. These notes are written by adding extra flags to the note stem.

If we need to write a note that’s in-between two durations, we can use a dot. A dot tells us to play the note + ½ of its value.

For example, a dotted quarter note lasts for one beat plus half a beat (one eighth note).

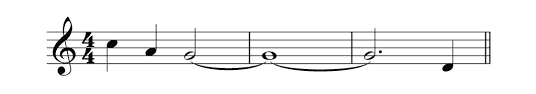

If the note sustains into the next measure, we use a tie. A tie is a curved line that tells us to combine the length of two written notes, and to play them as one continuous note.

When writing more than one eighth or sixteenth note next to one another, we can use a beam to connect them. This makes reading more orderly and easier to understand.

Just like notes have duration, so do rests.

Here is a helpful chart to explain the duration of rests when reading sheet music.

Time signature

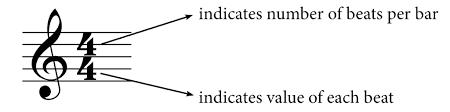

A piece’s time signature can be found next to the clef on the first bar in the staff. Bars are thin vertical lines that divide the staff. We use this framework like a grid to establish beat and rhythm.

A time signature has two numbers, one on the top and one on the bottom.

The top number tells us how many beats or pulses are in each measure or bar. The bottom number tells us which note length to count

as “one” beat.

The most common time signature is 4/4 time. In 4/4 time there are four beats, each lasting for one quarter note.

There is also 2/4 time, which contains two beats, both lasting for one quarter note.

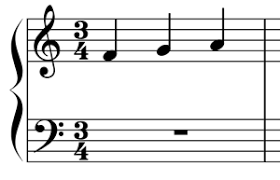

These time signatures are called “duple meter” because they are divisible by two (even numbers). There are also “triple meter” time signatures.

The most common triple-meter time signature is 3/4. 3/4 time contains three beats, all lasting for one-quarter note. This is most famously used in Waltz, a dance music genre that was wildly popular in the 19th century.

What happens if we combine duple and triple meter time signatures? The result is “compound” time signatures. Common compound time signatures are 6/8 and 12/8.

6/8 is famously used in doo-wop and classic soul, as well as rock and roll.

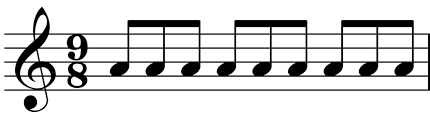

You might already recognize the pattern, but 6/8 time counts an eighth note as one beat instead of a quarter note. There are six beats per measure.

The final type of time signature is an “odd” time signature. Odd time signatures use an odd number of beats on top to create funky, disjointed rhythms. These time signatures are common in progressive music as well as jazz and world music.

Odd time signatures in 5/4, 7/4, 7/8, and 9/8.

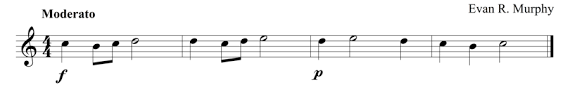

Here is an example of a riff in 9/8 time:

While most pieces of contemporary music are written in just one time signature, there is the possibility of a time signature changing midway throughout a piece, or even for one or two bars. This can be used creatively or to help the played music conform to the grid system of written notation.

For example, in pop music some producers will add an extra beat before the song’s final chorus for dramatic effect. This means we will need to account for that extra beat when writing down the music. If the song is in 4/4 time, we could change to 5/4 for just one bar. This lets us contain the extra beat neatly in one measure before we return to 4/4 time.

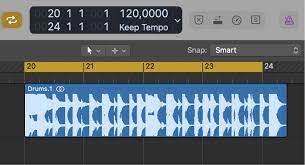

It’s important to understand time signatures as a producer and writer. With modern digital production being “to the grid”, time signatures are more relevant than ever.

Tempo

While a song’s time signature tells us how to count the notes within each measure, a song’s tempo tells us how generally fast or slow the song is.

In modern notation and production/writing, tempo is established with beats per minute or BPM. You’ll likely see this parameter at the top of a DAW or on a chart in the upper left hand corner.

A BPM of 60 would mean that one beat is played per second. While 120 would mean there are two beats played per second.

Classically, there are a slew of fancy Italian terms to try and communicate tempo.

Some of these are even more specific by denoting not only the speed at which the piece should be played, but also how it should feel when it is played.

Having a general idea of how these classical tempos feel will make you a more well rounded musician, so here is a helpful chart to connect the dots.

Key Signatures

Key signatures are a cluster of sharp or flat notes written next to the piece’s clef to help us read music more efficiently in different keys. These symbols tell us which notes to make sharp or flat when reading. Instead of having to write the individual accidental every time, the key signature tells us which notes will be raised or lowered throughout the entire piece.

Key signatures are commonly organized using the circle of fifths.

Melody

Now that we’ve learned about notes and rests, clefs, time signatures and tempo, we can begin to put everything together and start reading.

First notice the time signature. Then observe the melody to see where the notes go up in pitch and down in pitch. One by one, go through the pitches on your instrument. Next, add count through the rhythm. Finally, combine the pitches and rhythm as slowly as you need to so that the piece is perfectly in time.

From here, you can practice with a metronome to bring the line up to tempo.

Making this type of practice part of your daily routine pays huge dividends down the road. You’ll begin to read through scores and charts in a breeze, and unlock a whole new world of musical possibilities through notation.

Comments:

Login to comment on this post