What is Music Theory? The Basics Every Beginner Should Learn

Music theory is often maligned, misunderstood, or downright feared amongst musicians and non-musicians alike. Nevertheless, exploring theory can serve to enrich your enjoyment of music, help fuel your creative process and unlock some very mysterious doors, leading to an exciting and endless creative spark.

This article is for anyone with even the slightest interest or curiosity about learning music theory, and it’s designed to encourage you to explore your creativity through learning music theory. Don’t be afraid to read through until the end; it’s worth it.

If you’re beginning your journey, you will not grasp 100% of all of this, and that’s the point. Basic theory can create more questions than answers, and a complete primer like this will begin introducing concepts and musical vocabulary that will show up big time down the line. Keep reading and absorbing, and at some point, it’s all going to “click”.

What is music theory?

Simply put, music theory is the language with which we communicate musical ideas. It allows us to put our ideas into words, communicate those ideas with other musicians, and organize our thoughts, feelings, and propositions into a language that we all as musicians can understand. It’s a language that transcends national boundaries, cultures, religions, political views and when you look at it that way, one of the greatest achievements of humankind.

Music theory is a universal language, one that continues to evolve over thousands of years. It's part science, part math, and part art. In this article, we’re going to dive into the depths of beginner music theory, what it is, how it works, and how you can make it work for you.

Why should you learn music theory?

One of the biggest myths about creativity, as it pertains to music, is that learning music theory somehow could make you a less creative artist. This myth is a logical fallacy and just downright untrue. A greater command and deeper understanding of music theory add more tools to your kit and better equips you for various musical and compositional situations.

You may hear statements or read comments online about how legendary musicians like Kurt Cobain or Jimi Hendrix didn’t know theory and how it didn’t matter, but this also is partially untrue and irrelevant.

You see, Kurt, Jimi, and every other musician have at least some understanding of the fundamentals of their instrument and creative process, even if they speak a slightly different language.

My point here is that while Hendrix may not have known specific musical terminology or root rote fundamentals, he still had his own system and conceptual framework to fulfill his creative expression. He had a sufficient enough understanding of his craft to communicate his creative ideas effectively. Having more options at your disposal will never make you less creative, so never rule out learning theory based on this fear.

It’s important to note that while theory can be the cause and art or music the effect, theory is a language that we use to communicate our ideas and solve creative problems as they arise. This means that inspiration and expression will always take priority over following “rules”. However, having the theoretical knowledge to plug gaps in your creative process is indispensable and a must for any musician that aspires to great artistic achievement.

This is also an essential takeaway before we dive in: you don’t need to use all of the theory you know all the time. This is an express train to kill the creative process and sound like an encyclopedia.

Remember, theory is there to communicate effectively and to solve problems as they arise. Don’t invent problems for yourself to solve so that you can flex your skills. That’s what ToneGym is for... Follow your curiosity, invention, and spark, and let theory be the foundation that helps to support the fantastic skyscraper you’re fabricating.

How to learn music theory? - Traditional vs. Modern methods of learning

Traditional methods of learning music theory typically involve in-person training and education, either at school or with a private instructor. The Traditional Method has students learning to play an instrument early in life and learning to sight-read music simultaneously.

Other methods are used as well, such as the Orff method, which uses a multi-directional approach involving movement, speech, and improvising. The Kodály method believes that singing is the foundation of musical learning and teaches students using solfeggio and hand movements to sight-sing music.

From Baby Boomer to Millennials, many generations will have grown up learning theory from Walter Piston’s heavy three-volume tome: Harmony, Counterpoint, and Orchestration. This is combined with rigorous exercise in figured bass, voice leading, and composition, often without learning a musical instrument.

There are also the university methods, such as the Berklee method, which was developed by Lawrence Berk and often bucks against traditional guidelines of voice leading and harmony. These methods are best learned while attending said university and training under its professors.

With music programs becoming less and less prevalent at public schools, many students (and adults) may lack access to quality music education in the traditional manner. In addition, private lessons or studying at an expensive conservatory can be cost-prohibitive.

Enter the world wide web and its many gifts to democratize learning. Music education is now more accessible than ever, albeit a bit oversaturated. Modern methods include sites like ToneGym, YouTube videos, online lessons (group and private), and smartphone apps. With so many methods of learning theory to choose from today, knowing where to start can be an honest struggle.

You should explore and find a method you like, such as ToneGym's Music Theory 101: Interactive Crash Course, and stick with it for a while. Pulling from too many sources early on can make learning any new skill more challenging and confusing than necessary. While there are plenty of paths to follow, some may conflict with one another. While a more adept theoretician or creative person may be able to take what they like and leave the rest, it’s essential to have consistency and structure early on in your learning process.

That being said, if something isn’t working for you, don’t be afraid to drop it and find something else that gets better with your method of learning.

The basics of music theory

Music is made up of three fundamental parts; Melody, Harmony, and Rhythm.

Melody is a sequence of single musical notes arranged to please (or upset) the listener. Depending on their structure, melodies can feel happy, sad, angry, foreboding, dark, bright, goofy, or triumphant. We use melody to convey musical feelings or to carry a message using natural language (lyrics). We’ll elaborate on this shortly.

Harmony is the combination of different musical notes being sounded simultaneously. Harmony is used to enrich the melody, communicate our feelings more elaborately, and create movement or motion within the piece. In Western music, harmony is typically found in the form of chords (a group of three or more notes) and chord progressions (a series of chords played in sequence). These chord progressions have distinct sounds based on their arrangement, which set the tone of the music and the emotions conveyed to the listener.

Rhythm is the foundation for the message conveyed by a piece’s melody and harmony and expresses itself as a series of regular, repetitive sound patterns. Rhythm is how we keep time and create flow. Each element in a musical piece has rhythm, whether it’s the timing of the notes that comprise a song’s melody or the pattern of the chords played as harmony within a song.

In contemporary music, rhythm is often synonymous with drums or drum beats. This can come in the form of an acoustic drum kit, programmed electronic drums or MIDI drums, or things like handclaps and percussion (maracas, shaker, bongos).

When all three of these elements are present, we have music. Let’s take a look at a few examples and practice hearing this for ourselves.

Try listening to “Redbone” by Childish Gambino first and see if you can observe and identify melody, harmony, and rhythm throughout the piece on your own.

Right away, we can hear the drumbeat and bass guitar creating a steady pulse or rhythm that carries the song from the start. At the same time, a filtered guitar sound enters, playing a single note melody line. This melody is followed by another; Donald Glover’s vocals at 0:30. You can hear a soft, Wurlitzer-like piano providing chordal accompaniment by moving through a simple chord progression (the harmony) throughout the piece.

This famous piece by Richard Wagner contains all three of the core elements of music, only in ways that may be less easily identifiable to our modern ears. Let’s take a listen…

What did you hear?

It may be obvious that Ride of the Valkyries is music, but why? There aren’t any repetitive drum sounds or percussion to speak of or singing. Let’s take a closer look.

The pattern played by the soft horns at the very beginning of the piece creates a steady rhythm, interspersed with the falling and rising sound of the high strings, which also follow a repetitive, rhythmic pattern until 1:18. The melody is carried by the horns, with supporting harmony from the rest of the horn section and implied by the string parts' movement.

You’ll notice that percussion is used in this piece only as an accent (like at 2:08), not to carry or create the song’s rhythm, which is quite different from modern music, where the drums and cymbals are used most often to create a drumbeat or groove.

The rudiments of music theory

The music alphabet

Just like learning a spoken language, learning the musical alphabet is the first step in understanding the universal language of music. The musical alphabet uses characters from the standard English alphabet with a few additions such as # and ♭ (sometimes written using a lowercase letter “b”).

Here is the alphabet start to finish:

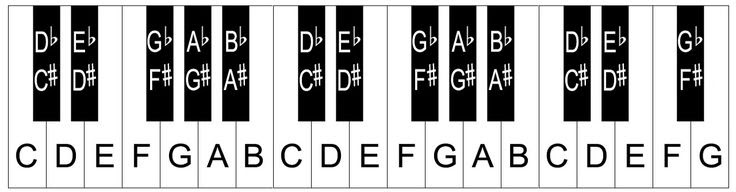

C - C#/D♭ - D - D#/E♭ - E - F - F#/G♭ - G - G#/A♭ - A - A#/B♭ - B

Look like gibberish? No sweat, it’s easy. The musical alphabet comprises 12 notes labeled with the letters A through G, but begins with the letter “C”. This is because the major musical key associated with “C” contains no sharp or flat notes, in other words, it contains all of the white keys on the piano. Therefore, this is considered “home base” when we begin a discussion about music theory.

Sharps (#) and flats (♭) are notes between notes. If we start on a white key and move up to a black key, the note is sharp. If we start on a white key and move down to a black key, the note is flat. These are called accidentals.

You may notice that some notes have two names! These notes sound exactly the same but can be labeled differently depending on context or the song’s musical key. The term for these notes is enharmonic. For example, you’ll notice that the black key between “F” and “G” can be labeled as “F#” or “G♭”. You’ll want to memorize these names.

The notes “E” and “B” don’t have sharp notes that follow them. This is because the current Western system of well-tempered tuning doesn't allow room for any additional notes (there are 12). Therefore, “E#” is just “F” and “B#” is “C”. Consequently, “C♭” is just “B” and “F♭” is just “E”. The only time “E#”, “F♭”, B#” or “C♭” appear is as a technicality when labeling some chords and scales.

Occasionally you may see a double flat (♭♭) or double sharp (x) sign. While these are quite uncommon, they do appear in some contexts. Don’t get hung up on this, as far as the basics go; you’re pretty much covered with knowing the standard series of sharps and flats.

Scales

A musical scale is a sequence of notes played in a specific order, according to the formula for the scale. Chords, progressions, melodies, and harmonies all come from scales, so they’re incredibly important to learn. The most important scale in Western music is the major scale (also called the Ionian mode). We use this scale as a point of reference when discussing music theory and constructing other scales.

Most scales in Western music contain seven (7) notes. A few notable exceptions include the pentatonic (five notes) and hexatonic (six notes) scales. These scales are borrowed from other musical systems, notably those of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa...

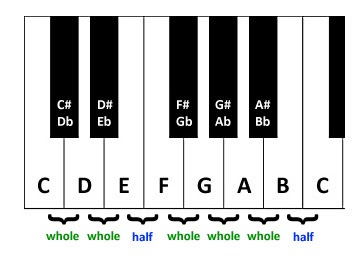

Diatonic scales in western are constructed from patterns of “whole” and “half” steps (also called whole tones and semitones). A whole step is two keys away on the piano (such as “D” to “E”), while a half step is just one key away on the piano (such as “C” to “C#”).

Here is the step formula for the standard “major” scale.

W W H W W W H

Applying this formula to the musical alphabet beginning on ANY note will create the corresponding major scale beginning on that note.

From this numerical perspective, the major scale is “spelled” 1 2 3 4 5 6 7. This is the most common way to refer to scales in theory, as this numbering could be applied to any scale in any key and produce the same result.

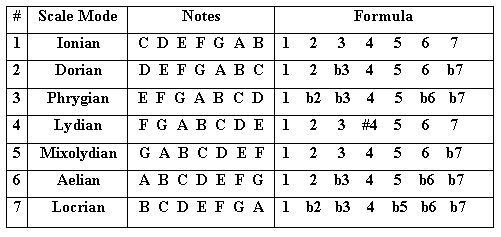

Each scale has six additional permutations called “modes”. A mode is created when the scale is played beginning and ending on a different note in the scale, other than the tonic. This rearranges the order of whole and half steps, thereby changing the sound and tonal quality of the mode.

For example, if we begin the “C” major scale on the 2nd note, “D” and play the notes from start to finish, we get a new scale called the “Dorian” mode.

D E F G A B C D

As you can see, the Dorian mode contains the same notes as the “C” major scale, only played in a different order. The order of whole and half steps is now: W H W W W H W. Because of this, the Dorian mode sounds very different from the “C” major scale. Many agree that it has a darker, more mysterious quality.

It’s important to see how we can synthesize the Dorian mode from the standard major scale (walk from one to another). If we apply the numbering nomenclature from above, we can see that the formula for producing the Dorian mode from the major scale is thus: 1 2 ♭3 4 5 6 ♭7. The difference between major and Dorian is the lowered or flattened 3rd and 7th scale degrees. Simply put, if we play the “C” major scale and lower the 3rd and 7th notes by one key or half step, we’ve built the Dorian mode beginning on the same note.

Here are the formulas for the rest of the “diatonic” scale modes in the key of “C”.

Scale degrees can also be written as Roman numerals like this: I ii iii IV V7 vi viio.

When expressed this way, uppercase numerals are used for major chords, while lowercase numerals are used for minor and diminished chords (more on that later).

Intervals

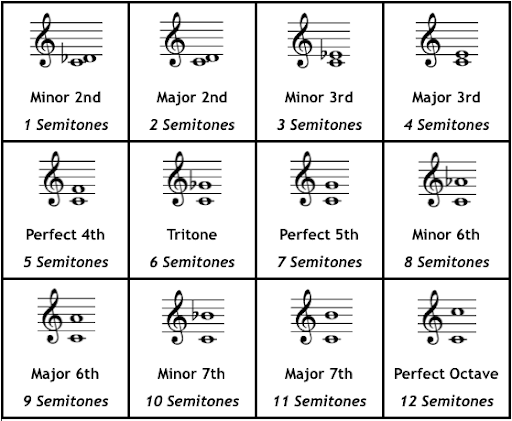

An interval is a term for the space or distance between two notes. Each interval has a unique sound, created by its relative distance from the tonic.

Intervals come in two types, consonant and dissonant. Consonant intervals like the “Perfect 5th” or “Major 3rd” are two notes with complimentary frequency patterns that resonate with each other.

They’re considered “stable” intervals because they don’t need to resolve. Dissonant intervals like the “Tri-tone” or “Minor 2nd” on the other hand, are two notes whose frequency patterns clash with one another, thereby creating a more jarring, unpleasant sound. Dissonant intervals are considered “unstable”, meaning they want to resolve to another, nearby consonant interval.

There are 12 basic intervals. These intervals are referenced often when discussing scales, chords and harmonies, and are indispensable to chord building, which we’ll take a look at next.

Chords

chords are built from scales using intervals. Standard chords contain three notes.

We are using the “C” major scale for reference: C D E F G A B C

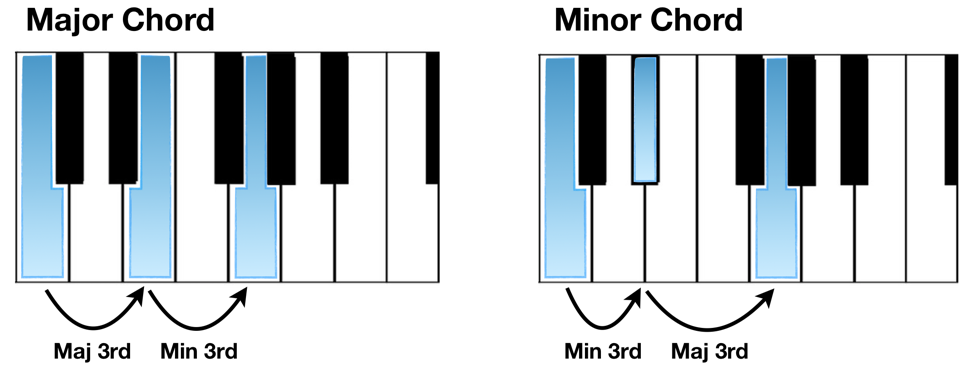

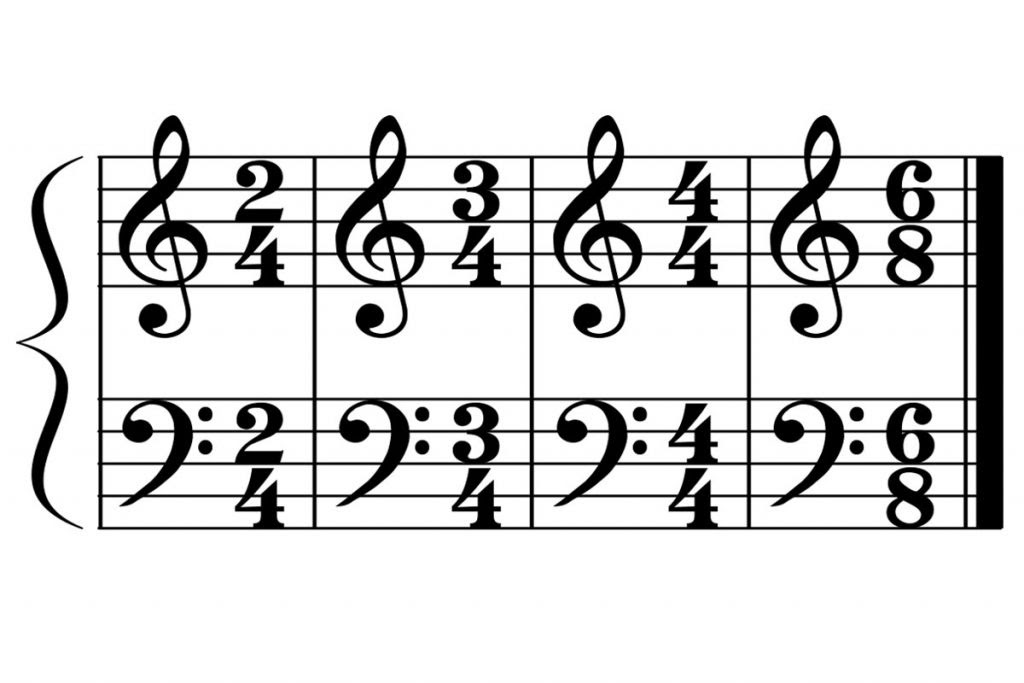

A major chord comes from placing a minor 3rd on top of a major 3rd. The distance between the bottom and top notes is a perfect 5th. A minor chord is created by lowering the 3rd by a half step, thus inverting the intervals so that the bottom of the chord is a minor 3rd and the top is a major 3rd.

We can also express this using numerology.

A major chord uses the formula 1 3 5: C D E F G A B C

The minor chord uses the same formula with the flattened/minor 3rd.

1 ♭3 5: C D E♭ F G A B C

These same formulas can be applied to other notes in the scale to build more chords in the key…

D minor: C D E♭ F G A B C

There are two other need-to-know chord types for beginners, diminished and augmented. These chords are dissonant and need to resolve back to another, harmonious chord.

A diminished chord is made up of two minor 3rd intervals; the perfect 5th then becomes a diminished 5th.

An augmented chord is made up of two major 3rds; the perfect 5th then becomes an augmented 5th.

A diminished chord uses the formula 1 ♭3 ♭5: C D E♭ F G♭ A B C

An augmented chord uses the formula 1 3 #5: C D E F G# A B C

When referring to the tonal quality of chords, we assume that a chord without any additional labeling such as minor, diminished, augmented or otherwise, is major. This means if you say, “the song starts on an F chord”, you are by default referring to “F” major. Unless you otherwise specify that the chord is minor, augmented or diminished, it will always default to major when written and spoken.

A diminished chord is written with “o” as in “Co” for “C” diminished. An augmented chord is written with the “+” sign as in “C+” for “C” augmented.

Key Signatures

A musical key is a group of pitches or the scale that forms the basis of a song’s harmonic structure. Keys are expressed as key signatures on written music notation. This key signature tells the musician which key the composition is in and, therefore, which notes will be sharp or flat. This eliminates the need to manually pencil in sharp and flat notes when writing music notation. We’ll talk about this a bit more in the next section.

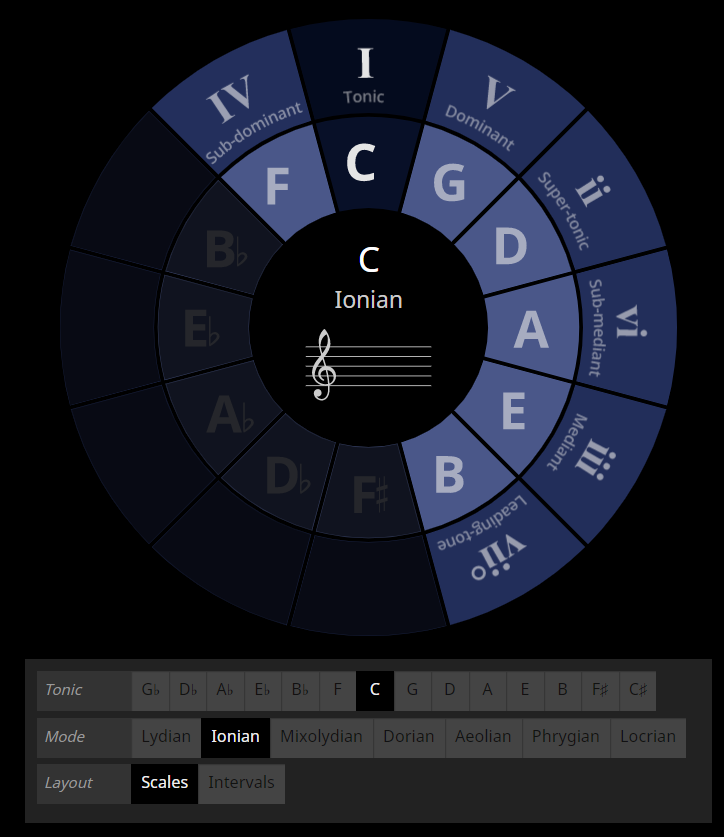

The circle of fifths (above) works to organize musical keys by placing the most closely related keys next to one another. This is a more intuitive way of understanding music theory than putting the keys in alphabetical order. Let me elaborate...

If we were to arrange the keys in sequential or chromatic order, things would get confusing quickly.

For example, if we start with the first key of “C” (spelled C D E F G A B C) and move up one-half step to the next key of ”C#” we would get a scale spelled C# D# E# F# G# A# B#.

These two major scales couldn’t have any less in common, in fact they don’t even contain ANY of the same notes.

However, if we start on ”C” and move up by a perfect 5th to “G” (the next key in the circle), something magical happens…

C D E F G A B C becomes G A B C D E F# G.

Notice anything? We’ve only added one sharp, F#, (which we can find two letters back within the circle).

If we continue this pattern and go from “G” to “D” we get D E F# G A B C#. Now we have two sharps, F# and C#. We can continue this pattern in perfect 5ths adding one sharp note to each key. This pattern repeats unto itself.

When we move through the circle backwards or counterclockwise, we get the descending “cycle of fourths”, or flat keys. Again, each consecutive flat key gains one flat note. At a certain point the flat and sharp keys will overlap. These are again called enharmonic keys, because they sound the exact same but can be labeled differently. Normally, the key that has the least number of accidentals is chosen out of convenience. For example, “A#” contains four sharp notes and three double sharp notes! Highly undesirable. The corresponding flat key of “B♭” major however, contains just two flat notes, making it much easier to read and write.

This comes into common practice in jazz, especially with horn and woodwind players; instruments like trumpet, saxophone, clarinet and trombone, who typically read music in flat keys. Reed and brass instruments were the pioneering voice of jazz and therefore, many jazz standards are written in the flat key as opposed to the enharmonic sharp key.

Each major key in the circle also has a corresponding “relative” minor key. This is the minor scale that contains the same notes as the relative major scale. For example, the “A” minor scale is spelled A B C D E F G A, without any sharps and flats, just like “C” major. These scales belong to the same key, and can be used interchangeably within the same key signature.

Sometimes, musicians will use notes from “outside” of the given key signature. This is especially common in jazz. In this case, accidentals for notes outside the key will be written into the manuscript manually.

Chord Progressions

A series of chords played in a specific order is called a chord progression. Chord progressions can range anywhere from two chords to dozens of chords. Chord progressions are typically represented by roman numerals and created using several chords taken from one key. Each musical key has chords as the number of notes in it, one built beginning on each note of the scale. Some common chord progressions are:

This chord comes from the Mixolydian mode. The chord built from the 5th scale degree of the major scale is always dominant.

1 3 5 ♭7: C D E♭ F G A B C

5 b7 1 3

Notation

Musical notation is the visual system with which we represent aurally perceived music. It is a tool that allows us to communicate our ideas with a unified system of code that other musicians can comprehend. It would be impossible to express the conceptual side of music theory with just notation, but it is an effective and necessary tool nonetheless.

We’ve already looked at a bit of notation, but here are a few more must-know terms and symbols.

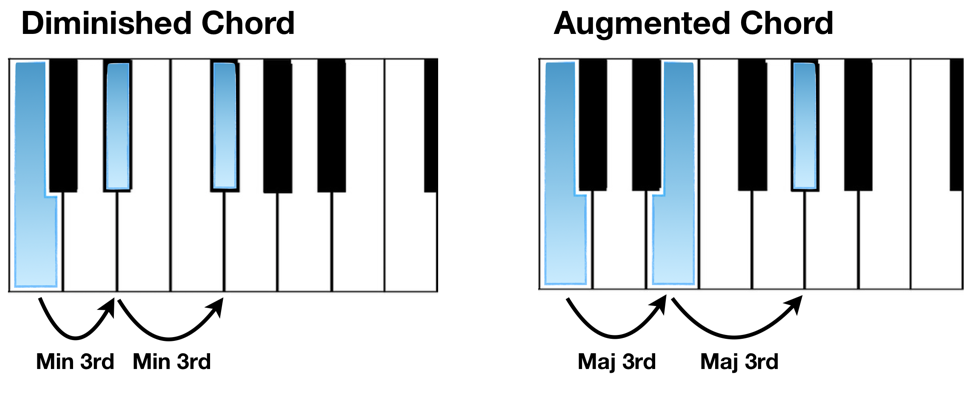

A clef indicates the pitches assigned to the lines and spaces on the music staff.

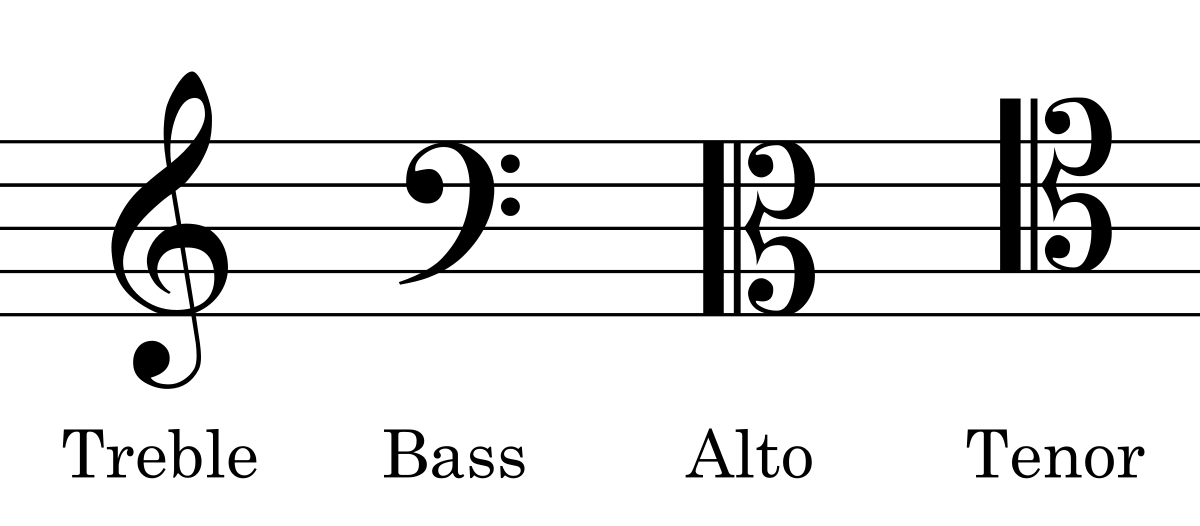

The piece’s time signature, written using two numbers stacked on top of each other, tells us how many beats are in each measure, and which note value counts as one beat. The top number is the number of beats, the bottom number is the note value. 4 = quarter note, 8 = eighth note. Therefore: 4/4 = 4 ¼ notes per measure.

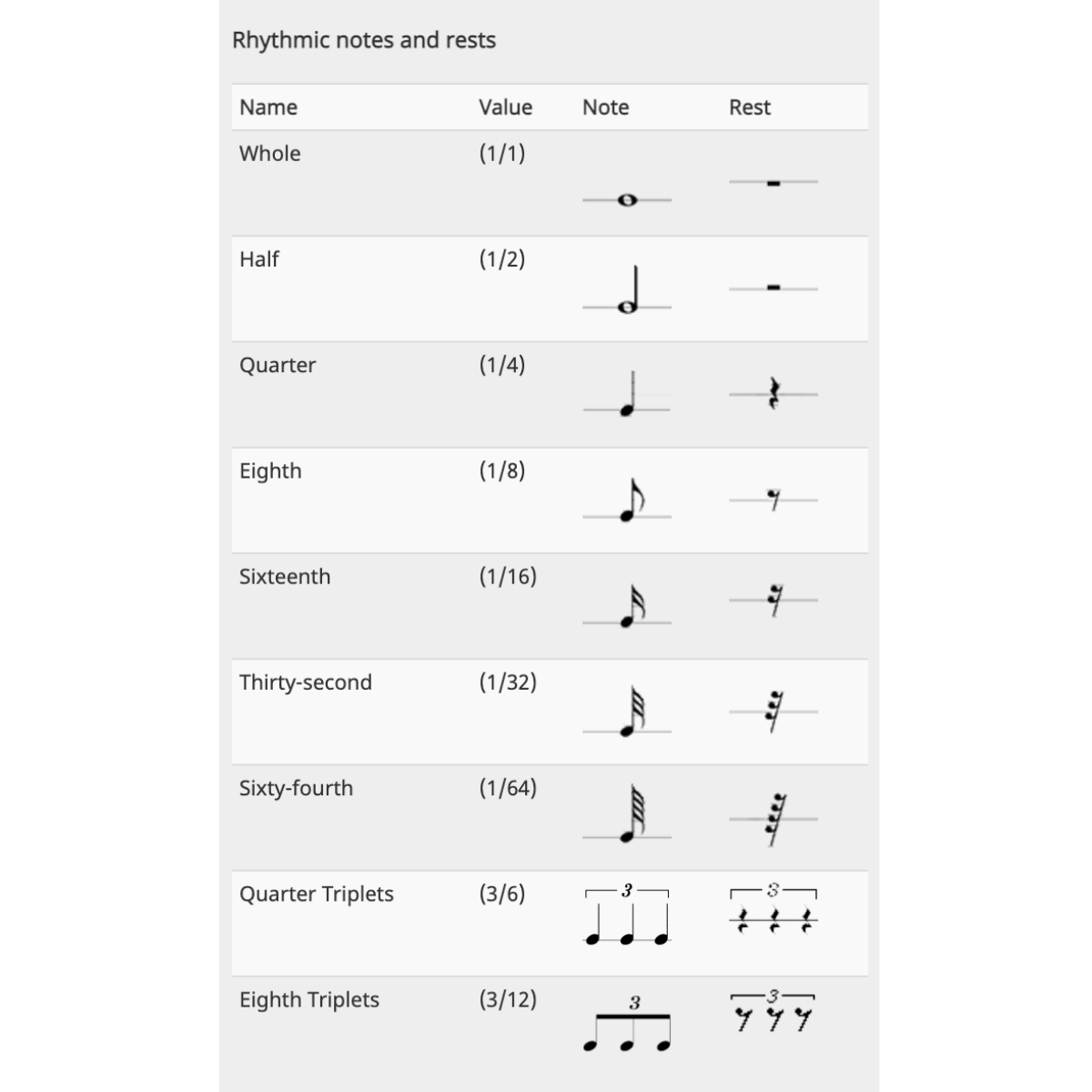

Pitches are written on the staff using notes, t. The notes have “stems” which indicate how long they are played for. Each note also has a corresponding “rest”, which is used to indicate space when the musician does not play.

A triplet is when three notes are squeezed into the space normally occupied by two notes.

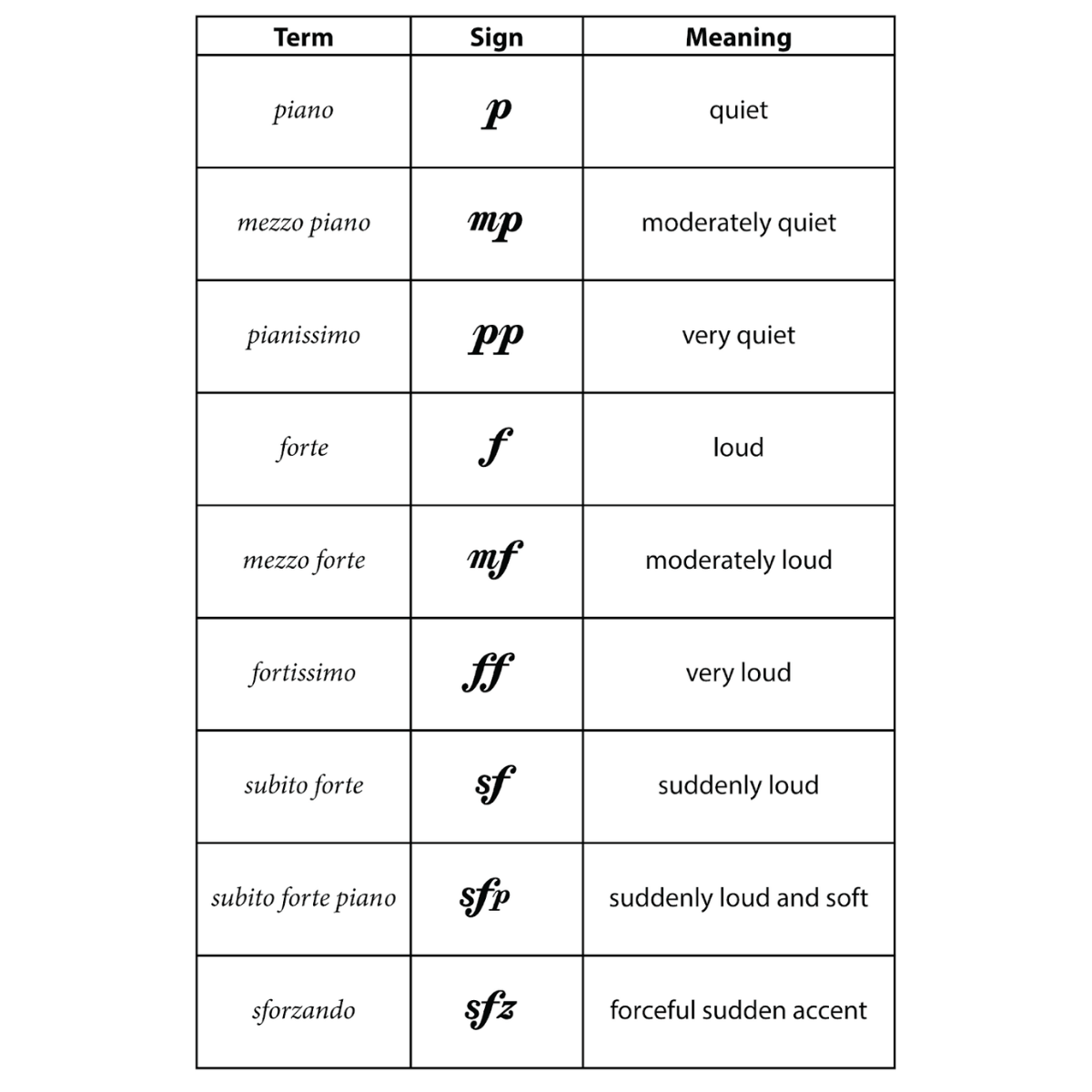

Dynamic markings (below) tell us how quietly or loudly a passage or piece is to be played.

The best way to internalize notation and connect sound with image is to practice in ToneGym using the Notationist game!

For a comprehensive list of music notation and symbology, you can check out our index here!

Music theory exercises

After a quick brain break, don’t hesitate to jump right in and put all of this into practice! The best way to learn music is to hear it, and interact with it, not read about it.

ToneGym is an incredible tool for grabbing some quick, deliberate practice, and to train your ears, eyes, and brain all at the same time.

Learning music theory, like anything else, takes time and practice, so please be kind to yourself as you embark on this journey of mastering a new and complex language. Music is a joy, and learning about it is nothing but fun. Go play!

Comments:

Login to comment on this post