The Blues Scale: How to Use it to Improve Your Music

Blues is the foundation of all of America’s great musical forms. Whether in Jazz, Rock, RnB or Hip-Hop, the undercurrents of the blues run-heavy. Every musician can benefit from learning more about blues and incorporating blues harmony, structures and rhythms into their own vocabulary or creative process.

Blues music evolved from African spirituals, shared by slaves and former slaves to express pain, hardship and the fight for freedom, while also serving as a vehicle for expressing joy, love and victory.

What is the blues scale?

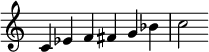

The hexatonic “blues” scale is probably the most widely found device leftover and in contemporary use from the blues tradition. Based on the standard pentatonic scale, the hexatonic scale is a six-note scale with an added b5 interval or “tri-tone”, as it’s commonly called in traditional music theory. This “blue” note adds tension to the pentatonic scale.

A melody written with this scale will sound decidedly “blues-y” and give your sound a nostalgic grit.

The standard pentatonic scale is very commonly used in contemporary melody writing. However, the hexatonic “blues” scale with a b5 in the melody is less common. Try incorporating this scale into your songwriting. And strengthen your ability to hear that distinctive tritone interval in ToneGym’s Interval game.

How to use the blues scale?

Call & Response

The technique of call and response has its roots in field chants and gospel music. One distinct musical phrase or “call” is answered by another distinct musical phrase or “response”. Here are some examples of call and response.

A very traditional example of call and response can be found in the great music of Chicago blues legend, Muddy Waters.

Muddy Waters - “Mannish Boy”:

The song’s intro features one of the greatest examples of call and response ever, as a twangy electric guitar responds to the call of Muddy Waters’ powerful voice. Muddy’s syrupy “Oh yeah”, is met with a biting guitar attack that compliments and plays off of each of Muddy’s vocalizations.

Harry Styles - “Adore You”:

In “Adore You” there is clear call and response in both the verses and choruses. If you listen in the verse, each line or “call” is answered by a “response” of the lines ending. In the chorus that follows the “ah ah ah” vocal part is answered by the chorus's main hook “walk through fire you, just let me adore you”.

One creative way to use this in your own process is to write vocal melodies with space. You can then choose to add “responses” in those sections on another instrument or separate vocal track, like in “Adore You”. Just make sure to listen closely to the call, and respond appropriately. Call and response isn’t about forcing two disparate musical ideas, it’s about creating a conversation between two instruments, voices, or both.

You could also try splitting a line or idea in half to create call and response.

Major & Minor 3rd

When writing or soloing with the minor pentatonic scale, a secondary “major” pentatonic scale can be constructed on the same root note, and used in the same melody or riff. Mind blown, I know.

Minor Pentatonic - 1 b3 4 5 b7

Major Pentatonic - 1 2 3 5 6

Spot any noticeable issues here? If these scales are used interchangeably, the melody or riff would have both a major AND a minor 3rd. This is a big no-no, but not in the blues. The tension and release created by the presence of both the major and the minor third is exhilarating, and opens up tons of wild possibilities when used as a tool to write melodies and in your improvisations.

A classic example of this is in the chorus melody of Michael Jackson’s hit “The Way You Make Me Feel”.

Michael Jackson - “The Way You Make Me Feel”:

You can hear this all throughout older blues and blues-influenced music, and especially in the soloing of B.B. King

B.B. King Live:

When soloing, the major pentatonic scale sounds especially good over the 4 chord. Speaking of 4 chords...

The 1 4 5 Chord Progression

The blues is built on the 1 4 5 chord progression, which can often become monotonous, as it is SO commonly used still in pop and contemporary music. However, there are some small changes we can make to give this progression new life.

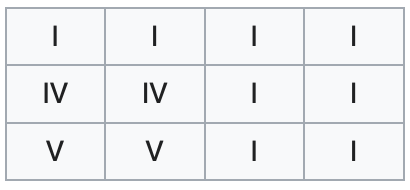

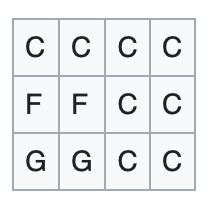

Here is a 12 bar blues form in both numeral notation, and in the key of “C”.

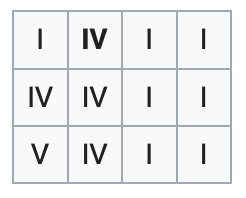

A common variant on the 12 bar blues is called “Quick Four”. Instead of staying on the 1 chord for four bars, you go to a “quick” 4 chord in bar 2.

Try using this quick change in a chord progression outside of the blues genre and see what happens. For example, you could add a quick one bar change into any chord progression you’re already familiar with, like a 1 6 4 5 etc.

If this sounds like French to you, brush up on your chordal prowess in ToneGym’s Chordelius and Route VI games.

AAB Rhyme Scheme

Traditional blues music uses an AAB rhyming scheme. The song structure is normally made up of several “verses”, where one line is sung twice with the same melody, over different chords, “AA”. The final line “B” is then sung with a different lyric/melody. A traditional example can be heard here in Sweet Home Chicago by Robert Johnson.

Robert Johnson - “Sweet Home Chicago”:

Hear how the first line is repeated? And then concludes with the “hook” line of “Sweet Home, Chicago”?

A creative way to use this technique in your writing could be to repeat a line twice, for emphasis, before departing for another (and possibly never returning). You could also try using the same finishing line in each verse of your song, but change the others!

You don’t need to use these techniques exactly as they are to get the creative boost and effect, always take what you like and leave the rest. Use these techniques in your way to finding new paths of invention and innovation.

Comments:

Jun 08, 2023

Jan 21, 2022

Login to comment on this post